Kudos to my nephew, Rob Campbell, and the innovative social media deck he’s helped launch at the Cleveland Indians’ ballpark, Progressive Field.

The Tribe Social Deck, believed to be the first of its kind in a major professional sports venue, is described as “a press box for bloggers/social media types.”

The Deck was launched last week at the team’s home opener.

As far as is known, Rob has been quoted as saying, “the Tribe Social Deck is a one-of-a-kind endeavor. Other professional sports teams have offered individual bloggers press credentials on occasion but to our knowledge there has never been a section exclusively catering to the internet and social media community.”

Rob heads up social media efforts for the Indians and posts frequently to the team’s Twitter site, Tribetalk.

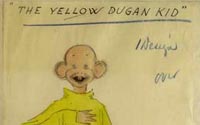

In other developments in social media, a writer for the BetaNews blog has proposed “yellow blogging” as a latter day “reincarnation” of yellow journalism, which flared in the U.S. press more than 100 years ago.

By “yellow blogging,” he means those “gossip and rumor blogsites [that] ruthlessly compete for pageviews.”

Cool term, “yellow blogging.” I like it.

But as heir to yellow journalism, as it was practiced in urban America at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century–unh-uh.

As I wrote in my 2001 book, Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies, “yellow journalism” has become a shorthand term–a cliché, really–for exaggerated, sensationalized, rumor-driven treatment of the news.

But that’s far from what “yellow journalism” was.

Newspapers of a century or so ago that can be classified as “yellow journals” (such as those of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer) “were, at a minimum, typographically bold in their use of headlines and illustrations,” I wrote in Yellow Journalism, adding:

“They certainly looked different from their gray, conservative counterparts, and their use of design elements was more conspicuous and imaginative. They were, moreover, inclined to campaign against powerful interests and municipal abuses, ostensibly on behalf of ‘the people.’ And they usually were not shy about doing so.”

More specifically, yellow journalism–a term that emerged in 1897–was defined by these features and characteristics:

- the frequent use of multicolumn headlines that sometimes stretched across the front page.

- a variety of topics reported on the front page, including news of politics, war, international diplomacy, sports, and society.

- the generous and imaginative use of illustrations, including photographs and other graphic representations such as locator maps.

- bold and experimental layouts, including those in which one report and illustration would dominate the front page. Such layouts sometimes were enhanced by the use of color.

- a tendency to rely on anonymous sources, particularly in dispatches of leading reporters.

- a penchant for self-promotion, to call attention frequently to the newspaper’s accomplishments.

So the yellow press back then was certainly anything but boring, predictable, or uninspired—complaints of the sort that frequently are raised about contemporary American newspapers.

The yellow journals were hardly wretched scandal sheets, indulging in gossip and rumor.