Media Myth Alert directed attention periodically in 2022 to the appearance of well-known media-driven myths, those prominent tales about the news media that are widely believed and often retold but which, under scrutiny, dissolve as apocryphal or wildly exaggerated.

Here’s a look at the year’s five top posts at Media Myth Alert, a year in which myths associated with the 50th anniversary of the origins of the Watergate scandal figured conspicuously, although not exclusively. (The demands of other projects necessarily trimmed the volume of blog posts in 2022.)

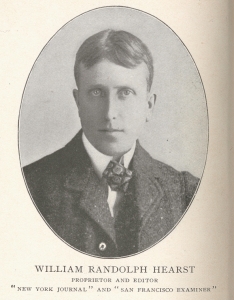

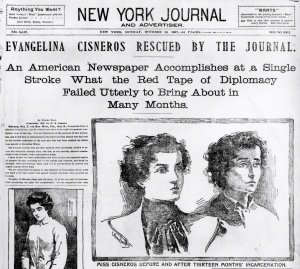

■ ‘I’ll furnish the war’: 25 reasons why it’s a towering media myth (posted January 10): William Randolph Hearst’s supposed vow to “furnish the war” with Spain at the end of the 19th century is one of the best-known anecdotes in American journalism. The aphorism has been presented as genuine in innumerable histories, biographies, newspaper and magazine accounts, broadcast reports, podcasts, and essays posted online.

And yet, the evidence is overwhelming that Hearst made no such pledge.

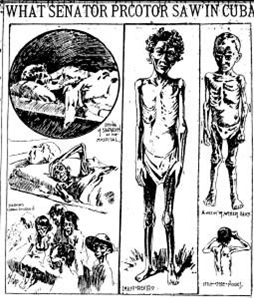

On assignment for Hearst, 1897

Media Myth Alert thoroughly dissected the tale in January, at what would have the 125th anniversary of the Hearstian vow, had it been made.

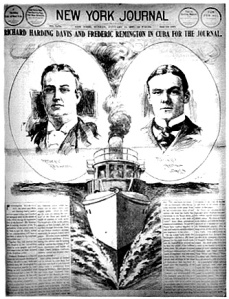

Among the 25 reasons presented in the post was that the artifact — a telegram from Hearst to the artist Frederic Remington that supposedly contained the pledge — has never turned up.

The anecdote — which I have examined in my media-mythbusting book Getting It Wrong and in an earlier work, Yellow Journalism — founders on an internal inconsistency. That is, why would Hearst pledge to “furnish the war” when war — the island-wide Cuban rebellion against Spain — was the very reason he sent Remington to Cuba in the first place? The armed struggle had begun in February 1895, or almost two years before Remington traveled to Cuba to draw illustrations of the conflict for Hearst’s New York Journal.

Despite its repeated debunking, the tale lives on, largely because it represents apparent evidence for the notion that Hearst and his newspapers fomented the Spanish-American War. That dubious, media-centric interpretation is, however, endorsed by no serious contemporary historian of that war.

Not only that, but Hearst denied making such a statement. So, too, did his son, William Randolph Heart Jr. In a memoir published in 1991, the son wrote:

“Pop told me he never sent any such cable. And there has never been any proof that he did.”

■ WaPo review indulges in myth, claims Bernstein’s ‘work brought down a president’ (posted January 16): The Washington Post published in mid-January a glowing review of Chasing History, Carl Bernstein’s memoir about his early days in journalism. A passage in the review said Bernstein’s “work brought down a president” — a reference to the popular and irrepressible “heroic-journalist myth” of the Watergate scandal of 1972-74.

The myth has it that Bernstein and his Post colleague, Bob Woodward, uncovered in their tireless reporting evidence that forced President Richard Nixon’s resignation in Watergate.

WJC and Woodward, at the Watergate in 2022

The brought-down-a-president claim not only is mythical; it runs counter to unequivocal denials by the likes of Katharine Graham, the Post’s publisher during the Watergate period.

At the 25th anniversary of the seminal crime of Watergate — the foiled break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington in June 1972 — Graham declared at a program at the former Newseum in suburban Washington:

“Sometimes, people accuse us of bringing down a president, which of course we didn’t do, and shouldn’t have done. The processes that caused [Nixon’s] resignation were constitutional.” She was broadly alluding to the work of investigative bodies such as panels of both houses of Congress, special prosecutors, federal judges, the FBI, and the Supreme Court.

In earthier but no less unequivocal terms, Woodward also disputed the heroic-journalist interpretation of Watergate, once stating in an interview with the now-defunct American Journalism Review:

“To say that the press brought down Nixon, that’s horse shit.”

■ They ‘lit the kindling’: New memoir exaggerates Woodward, Bernstein’s agenda-setting effect in Watergate (posted October 25): A variant of the tenacious “heroic-journalist” myth is that Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate reporting had important agenda-setting effects. This, too, is a dubious interpretation. But it found expression in a memoir by the Post’s former media columnist Margaret Sullivan.

She claimed their Watergate reporting “lit the kindling” that set off investigations that brought down Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Sullivan

The Woodward-Bernstein agenda-setting effect in Watergate was weak at best. The influence of their reporting, if it much existed at all, was shared influence.

Woodward and Bernstein had plenty of company in reporting on the unfolding Watergate scandal in the summer and fall of 1972.

While Woodward and Bernstein did some commendable reporting during those early days — such as tying the likes of former Attorney General John Mitchell to the scandal — other corporate news outlets scored significant beats as well.

The New York Times was first to report about the repeated phone calls placed to Nixon’s reelection campaign by one of the five burglars arrested June 17, 1972, inside Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. The calls were made before the break-in, which was the crime that touched off the scandal.

One way to gauge Woodward and Bernstein’s agenda-setting effects is to seek traces of their reporting in the three articles of impeachment drawn up against Nixon by the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives. (Nixon resigned the presidency before the House could act on the articles of impeachment.)

Garrett M. Graff, author of the book Watergate: A New History, which came out early in the year, has pointed out that the articles of impeachment did not reflect Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting.

“In the end,” Graff wrote, “none of the Post’s exclusives through the summer and fall of 1972 would be part of the narrative told by a House committee in 1974 as it drew up its three articles of impeachment for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress.”

Graff characterized the impact of Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting as “subtle, less revelatory in the moment than it seemed in hindsight.”

Thin kindling, in other words.

■ How ‘alone’ was WaPo in reporting emergent Watergate scandal? Not very (posted May 30): Before her retirement, Sullivan made another dubious claim about the Post’s Watergate reporting, declaring in a column that Woodward and Bernstein “were almost alone on the story for months.”

That, too, is another misleading element in the media lore of Watergate.

As I pointed out in Getting It Wrong, the Post certainly had company: “rival news organizations such as the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times did not ignore Watergate as the scandal slowly took dimension during the summer and fall of 1972.

“The Los Angeles Times, for example, published an unprecedented first-person account in early October 1972 by Alfred C. Baldwin III, a former FBI agent who had acted as the lookout man in the Watergate burglary.”

As Edward Jay Epstein noted in his classic essay for Commentary about the press and Watergate, the Post and other newspapers were joined in the summer of 1972 by the General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, and Common Cause, a foundation promoting accountability in government, in calling attention to the emergent scandal.

Moreover, the Democratic National Committee filed a civil lawsuit against Nixon’s reelection committee, the Committee to Re-elect the President, which ultimately compelled statements under oath.

And Nixon’s Democratic opponent for president, George McGovern, often invoked Watergate in campaign appearances in summer and fall of 1972. At one point, McGovern charged that Nixon was “at least indirectly responsible” for the Watergate burglary. And McGovern termed the break-in ‘the kind of thing you expect under a person like Hitler.’”

So, no, the Post was very much not alone in reporting the emergent Watergate scandal.

Moreover, as Epstein wrote in Commentary a month before Nixon resigned in 1974, “the fact remains that it was not the press which exposed Watergate; it was agencies of government itself.”

■ Watergate footnote: WaPo’s Pulitzer-winning entry included a false story (posted August 21): Media Myth Alert contributed an intriguing footnote to the Watergate saga with a post addressing a little-known oddity in the Post’s entry that won a Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for reporting about the emergent scandal.

The Post’s entry included an article by Bernstein and Woodward that proved false.

Media Myth Alert previously was unaware that a false story had been part of the Pulitzer-winning package.

The false report was published October 6, 1972, on the Post’s front page beneath the headline:

“Bug memos sent to Nixon aides.”

In the article, Bernstein and Woodward identified by name three men associated with Nixon’s White House or his reelection campaign. The trio supposedly had been sent “memos describing wiretapped conversations of Democratic Party officials” at offices of Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex in Washington. The illegal wiretaps had been planted in late May 1972.

As it turned out, none of the men had been sent the wiretap memos. In other words, they had been falsely accused by Bernstein and Woodward — as the journalists acknowledged in All the President’s Men, their 1974 memoir about reporting the Watergate scandal.

So how did the “Bug memos” article come to be part of the Post’s Pulitzer-winning entry?

That’s a mild mystery, and Media Myth Alert — no friend of the notion that Bernstein and Woodward’s reporting brought down Nixon — doesn’t believe the Post intentionally entered a false report.

More likely, the “Bug memos” article was thought credible at the Post until sometime after the submission deadline for Pulitzer entries in 19 73. The deadline that year was February 1.

73. The deadline that year was February 1.

As late as January 20 that year, the Post’s reporting on Watergate indicated its belief the “Bug memos” story was accurate.

While it wasn’t a major Watergate story, “Bug memos” turned out to be a story in major error. And a search of Washington Post contents at the ProQuest historical newspapers database does not indicate that it was specifically corrected by the newspaper.

The correction, as it were, appeared in All the President’s Men, which was published in June 1974, about 20 months after the “Bug Memos” article appeared.

“Three men had been wronged,” Bernstein and Woodward wrote in the book. “They had been unfairly accused on the front page of the Washington Post, the hometown newspaper of their families, neighbors, and friends.” Bernstein and Woodward said in the book they “[e]ventually became convinced” that memos the three men received “had nothing to do with wiretapping.”

Declared the essay: “When you see talking heads uncritically parroting propagandist stories about Ukraine that turn out to be false … you should be asking why the corporate media is so willing to spread such fake news …. It wouldn’t be the first time the press lied to pull Americans into war.”

Declared the essay: “When you see talking heads uncritically parroting propagandist stories about Ukraine that turn out to be false … you should be asking why the corporate media is so willing to spread such fake news …. It wouldn’t be the first time the press lied to pull Americans into war.”

In September, at the 20th anniversary of the attacks, the

In September, at the 20th anniversary of the attacks, the

ead portions of Cleeton’s novel and was struck by the reminiscence to details first described in my 2006 book,

ead portions of Cleeton’s novel and was struck by the reminiscence to details first described in my 2006 book,

As he had

As he had