The Boston Herald published an odd commentary the other day, one that scoffed at core elements of the media myth of the “Cronkite Moment” of 1968 while repeating the dubious elements anyway.

Cronkite in Vietnam

Such can be the appeal of media-driven myths, those apocryphal or improbable tales about powerful media influence: They can be too compelling to resist and as such invite comparisons to the junk food of journalism.

The Herald’s commentary discussed the mythical “Cronkite Moment” as historical context in considering the lies told about the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, which may have permanently damaged Joe Biden’s beleaguered presidency.

The commentary asserted:

“Back in 1968 widely respected CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite reported that the controversial war in Vietnam, which had so divided the country, was lost, hopelessly ‘mired in stalemate.’

“Coming from Cronkite, a battle-hardened World War II reporter, deemed the most trusted newsman on television, the report shook the foundations of the [Lydon] Johnson administration.

“Such was Cronkite’s influence.

“Johnson, following the broadcast, reportedly said, ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the war.’ Or ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost America.’ Or ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.’

“There is no proof that Johnson said any of those things, or if he even watched the broadcast.

“But that was what was reported. The myth took hold and weeks later Johnson, who had repeatedly lied to the American people about the war, announced that he would not seek re-election.”

It’s puzzling why a commentator would enlist media myths to illustrate an argument; invoking a dubious tale, after all, brings neither strength nor clarity to that argument.

In any case, there’s much to unpack in the the Herald’s commentary, which overstates Cronkite’s influence as well as the significance of his remarks made in closing an hour-long televised report on February 27, 1968, about the war in Vietnam.

Cronkite that night did not claim the war was lost; he said the U.S. military effort there was “mired in stalemate.”

Such an assessment was no daring or original analysis about the war; other U.S. news organizations had invoked such a characterization months before Cronkite’s program. The New York Times, for example, declared in a front-page analysis on August 7, 1967, that “the war is not going well. Victory is not close at hand. It may be beyond reach.”

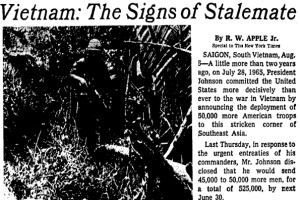

The Times report by R.W. Apple Jr. was published on its front page beneath the headline:

Vietnam: The Signs of Stalemate.

Even sterner critiques were in circulation in late February 1968. Four days before the Cronkite program aired on CBS, the Wall Street Journal said in an editorial that the U.S. war effort in Vietnam “may be doomed” and that “everyone had better be prepared for the bitter taste of defeat beyond America’s power to prevent.”

Not stalemated.

Doomed.

Not only was Cronkite’s assessment that night in 1968 unoriginal; it prompted no acknowledged policy shift in Johnson’s Vietnam policy — let alone having shaken the administration’s “foundations.”

It is certain that Johnson did not see the Cronkite program when it aired. The president was at a black-tie birthday party in Texas at the time and it is unclear whether, or when, he watched it afterward on videotape. This is significant because presumed impact of the “Cronkite Moment” resides in its sudden, unexpected, and visceral effect on the president: Such an effect would have been absent, or significantly diluted, had Johnson seen the program on videotape at some later date.

Moreover, In the days and weeks after Cronkite’s program, Johnson was aggressively and conspicuously hawkish in his public statements about the war — as if he had, in effect, brushed aside Cronkite’s downbeat assessment to rally popular support for the war effort. He doubled down on his Vietnam policy and at one point in mid-March 1968 called publicly for “a total national effort” to win the war.

Not only that, but U.S. public opinion had begun to shift against the war long before Cronkite’s report. Polling data and journalists’ observations indicate that a turning point came in Fall 1967.

Indeed, it can be said that Cronkite followed rather than led Americans’ changing views about Vietnam

Johnson’s surprise announcement on March 31, 1968, that he would not seek reelection to the presidency pivoted not on what Cronkite had said on television but on the advice of an informal group of foreign policy experts and advisers known as the “Wise Men.” Days before the announcement, the “Wise Men” had met at the White House and, to the president’s astonishment, opposed escalating the conflict as Johnson was contemplating.

One of the participants, George Ball, later recalled: “The theme that ran around the table was, ‘You’ve got to lower your sights’” in Vietnam.

The president, Ball said, “was shaken by this kind of advice from people in whose judgment he necessarily had some confidence, because they’d had a lot of experience.”

Cronkite was not at the table of “Wise Men.” By then, his unremarkable commentary about the war was a month old.

Marginal at best: such was Cronkite’s influence on Vietnam policy.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- Cronkite did all that? The anchorman, the president, and the Vietnam War

- ‘When I lost Cronkite’ — or ‘something to that effect’

- Maureen Dowd misremembers the ‘Cronkite Moment’

- Chris Matthews invokes the ‘if I’ve lost Cronkite’ myth in NYT review

- WSJ columnist, trying to explain Trump, trips over Cronkite-Johnson myth

- Newsman tells ‘a simple truth,’ changes history: Sure, he did

- LBJ’s ‘Vietnam ephipany’ wasn’t Cronkite’s show

- No, WaPo: Nixon never ‘touted a secret plan to end war in Vietnam

- Of media myths and false lessons abroad: Biden’s Moscow gaffe

- List of flubs by pols incomplete without Biden’s Watergate gaffe

- An easy caricature: PBS portrait of medial mogul Hearst is unedifying, superficial

- Recalling George Romney’s ‘brainwashing’ — and Gene McCarthy’s ‘light rinse’ retort

- Even in a pandemic, media myths play on

- The shame of the press

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

[…] ‘Such was Cronkite’s influence’ […]