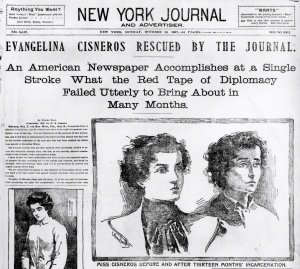

American journalism’s most famous jailbreak narrative — the escape of Evangelina Cisneros from a Havana prison in October 1897 — once again has demonstrated remarkable and enduring appeal.

The jailbreak, which was organized by a Havana-based reporter for William Randolph Hearst’s brash New York Journal, is the centerpiece of a recently published fictional account — the third treatment by a novelist since the early 1990s.

The rescue of Cisneros, then a teenage political prisoner, represented the zenith of Hearst’s “journalism of action,” a paradigm that envisioned newspapers taking high-profile participatory roles in addressing, and remedying, wrongs of society.

The jailbreak is central to Chanel Cleeton’s The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, which was published early this month. It also was a narrative centerpiece of Daniel Lynch’s amusing if improbable Yellow, which was published in 1992, and of Amy Ephron’s White Rose, which came out in 1999 and was billed as part romance, part thriller.

I r ead portions of Cleeton’s novel and was struck by the reminiscence to details first described in my 2006 book, The Year That Defined American Journalism: 1897 and the Clash of Paradigms. (I also reported findings about the jailbreak in an article, “Not a Hoax: New Evidence in the New York Journal’s Rescue of Evangelina Cisneros,” that was published in 2002 in the peer-reviewed scholarly journal American Journalism.)

ead portions of Cleeton’s novel and was struck by the reminiscence to details first described in my 2006 book, The Year That Defined American Journalism: 1897 and the Clash of Paradigms. (I also reported findings about the jailbreak in an article, “Not a Hoax: New Evidence in the New York Journal’s Rescue of Evangelina Cisneros,” that was published in 2002 in the peer-reviewed scholarly journal American Journalism.)

Cleeton, however, acknowledges no debt to The Year That Defined American Journalism, which specifically rejected the persistent but evidence-thin notion that the jailbreak was a hoax, that Cisneros was freed because Spanish authorities then ruling Cuba had been bribed to look the other way.

I wrote in The Year That Defined American Journalism that the Cisneros jailbreak instead was “the successful result of an intricate plot in which Cuba-based operatives and U.S. diplomatic personnel filled vital roles” — roles that had remained obscure for more than 100 years.

To her credit, Cleeton does not embrace the jailbreak-as-hoax notion.

But her discussion of the main actors who conspired to break Cisneros from jail certainly would be familiar to readers of The Year That Defined American Journalism.

Cisneros in 1898

Indeed, several characters discussed in The Year That Defined American Journalism figure in Cleeron’s novel.

They include:

Karl Decker, the jailbreak’s organizer who nominally was the Journal’s correspondent in Havana; Carlos Carbonnel, the Cuban-American banker who secluded Cisneros at his home after the jailbreak and who married her several months later; Walter B. Barker, the headstrong U.S. consular officer in north-central Cuba who acted as Cisneros’ guardian aboard the New York-bound steamer on the final leg of her escape from Havana, and William B. MacDonald and Francisco (Paco) DeBesche, who were Decker’s accomplices in the jailbreak.

Several previously undisclosed details about the Cisneros escape were found in my review of an unpublished manuscript of Fitzhugh Lee, the senior U.S. diplomat in Cuba from 1896 until the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898. The manuscript offered insights “not to be found in other sources,” I noted in The Year That Defined American Journalism.

Lee’s manuscript and his other papers at the University of Virginia — which, at my urging, were opened to scholars in 2001 — also make clear that he, his wife, and daughter took exceptional interest in the plight of Cisneros (whose full name was Evangelina Cossio y Cisneros).

At the time of her escape, she was 19-years-old and had spent 15 months in captivity in Havana’s notorious jail for women, Casa de Recogidas, without being tried.

She was suspected by Spanish authorities of complicity in an assault on a senior Spanish officer on the Isle of Pines (now the Isle of Youth); Cisneros said the officer, Colonel José Bérriz, had made unwelcome advances toward her. The Cisneros case unfolded during the Cuban rebellion against Spain’s colonial rule, an insurgency that began in 1895 and had spread across Cuba by 1897.

Spanish authorities imposed harsh conditions on Cubans in a failed attempt to put down the rebellion, which eventually brought U.S. intervention and the Spanish-American War.

His manuscript suggests that Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of the Confederate general Robert E. Lee, was aware of the plot to free Cisneros. But he had plausible deniability, given that he was on home leave in the United States when Cisneros escaped in the small hours of October 7, 1897.

Two days later, Cisneros was dressed as a boy and brought aboard the steamer Seneca, which reached New York October 13.

In keeping with his paradigm of activist journalism, Hearst organized a thunderous outdoor reception for Cisneros and Decker, who, under an assumed name, had separately fled Cuba aboard a Spanish-flagged vessel. Nearly 75,000 people came to Madison Square, a turnout the Journal described as “the greatest gathering New York has seen since the close of the [civil] war” in 1865.

The jailbreak and flight of Evangelina Cisneros make for a remarkable story, one without direct equivalent in American journalism. It is a complex and untidy narrative, too. As I wrote in The Year That Defined American Journalism, “to examine the Cisneros affair in any detailed way is to confront a tangle of contradiction, exaggeration, and misdirection.”

Scrubbing jailhouse floors (New York Journal)

The Journal, for example, probably exaggerated the conditions of her confinement, suggesting that among other indignities she was commanded to scrub the jailhouse floors. Fitzhugh Lee publicly scoffed at such accounts.

Cleeton hinted at the complexity of the jailbreak narrative, writing in an author’s note at the close of her novel, “There were times in telling Evangelina’s story that truth felt stranger than fiction,” adding that “there was no need for dramatic embellishment.”

She said her primary source was The Story of Evangelina Cisneros, which the Journal had arranged for publication in late 1897, based on reporting by Decker and others. The book, however, contained almost no detail about the plot to free her; no reference by name to Decker’s co-conspirators; no specific mention of Carlos Carbonell, the bachelor-banker who, as Lee’s manuscript makes clear, was vital to the success of the covert operation.

Story of Evangelina Cisneros was the only work cited specifically by Cleeton, who she said she “utilized” more than 100 sources “to research different aspects of the novel.”

Given the novel’s reliance on details first published in The Year That Defined American Journalism, acknowledging the book by name would have been fitting.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- Was ‘jailbreaking journalism’ a hoax? Evidence points the other way

- Recalling American journalism’s greatest escape narrative

- Yellow journalism: A sneer is born

- The ‘anniversary’ of a media myth: ‘I’ll furnish the war’

- Hearst, agenda-setting, and war

- Nat Geo’s cartoonish treatment of Hearst v. Pulitzer

- Recalling George Romney’s ‘brainwashing’ — and Gene McCarthy’s ‘light rinse’ retort

- Mythmaking in Moscow: Biden says WaPo brought down Nixon

- Even in a pandemic, media myths play on

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

[…] The enduring and impressive appeal of journalism’s most famous jailbreak narrative […]

[…] The impressive and enduring appeal of journalism’s most famous jailbreak narrative […]

[…] The impressive and enduring appeal of journalism’s most famous jailbreak narrative (posted May 29): The remarkable and enduring appeal of American journalism’s most famous […]