In the weeks since Russia launched its brutal and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, a critique has tentatively emerged that hawkish media commentary is intended to push the United States to intervene in the conflict.

U.S. military intervention is a very remote prospect and the critique was only murmured before gaining full-throated expression the other day in an essay posted at the Federalist website beneath this feverish headline:

“The press has lied to drag the United States into war before. Don’t think they won’t again.”

Declared the essay: “When you see talking heads uncritically parroting propagandist stories about Ukraine that turn out to be false … you should be asking why the corporate media is so willing to spread such fake news …. It wouldn’t be the first time the press lied to pull Americans into war.”

Declared the essay: “When you see talking heads uncritically parroting propagandist stories about Ukraine that turn out to be false … you should be asking why the corporate media is so willing to spread such fake news …. It wouldn’t be the first time the press lied to pull Americans into war.”

What followed was a superficial history lesson that rested on the media myth that overheated newspaper coverage — particularly in the aftermath of the destruction of the battleship Maine in Havana’s harbor in February 1898 — pushed the country into war with Spain that year.

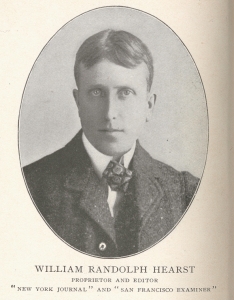

Almost predictably, the essay turned for support to a related media myth, that of William Randolph Hearst’s purported pledge to “furnish” a war with Spain.

“As the story goes,” the Federalist stated, “in the year before the Maine exploded, Hearst had commissioned reporter Frederic Remington to go to Cuba, where Cuban revolutionaries were skirmishing with their Spanish colonizers. When Remington sent Hearst a wire to explain he was leaving Cuba because there was no war to cover, Hearst reportedly replied, ‘You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.'”

The “furnish the war” anecdote has been thoroughly debunked, as readers of Media Myth Alert are aware. Qualifying the anecdote’s use with “reportedly” in no way lets the essayist off the hook for repeating an utterly dubious tale.

So let’s unpack the Federalist’s exaggeration-studded claims about Remington, Hearst, Cuba, and war.

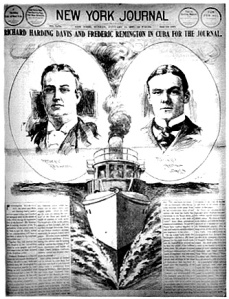

Cuban insurgents were engaged in much more than “skirmishing with their Spanish colonizers” when Remington, an artist, traveled to the island in January 1897. He was on assignment from Hearst’s New York Journal to sketch scenes of an armed struggle that had begun in 1895. The Cuban guerilla war against Spanish rule was no trivial matter, no mere “skirmishing.”

Such a notion is belied by the sketches Remington drew during his brief stay in Cuba. The artist’s sketches, which were given prominent display in the Journal, depicted such scenes as a scouting party of Spanish cavalry with rifles at the ready; a cluster of Cuban non-combatants trussed and bound and being herded into Spanish lines; a scruffy Cuban rebel taking aim at a small Spanish fort; a knot of Spanish soldiers dressing a comrade’s leg wound, and a formation of Spanish troops firing at insurgents.

While they weren’t Remington’s best work, the sketches made clear that he had seen war-related turmoil and violence in Cuba. There was indeed a “war to cover” when he was there.

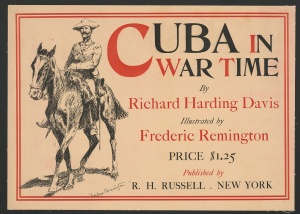

And “war” was commonly invoked then to described the conflict. Remington’s travel companion to Cuba, Richard Harding Davis, turned readily to that word.

Remington, Davis in Cuba for Hearst

Davis, a self-absorbed novelist, playwright, and aspiring war correspondent, declared in a letter from Cuba in mid-January 1897, for example: “There is war here and no mistake.” (Later in 1897, Davis repurposed the dispatches to Hearst’s Journal as a book titled Cuba in War Time.)

War in Cuba had reached island-wide dimension by early 1897; he U.S. consul-general in Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, reported in February 1897 that Spanish forces had pacified not one Cuban province.

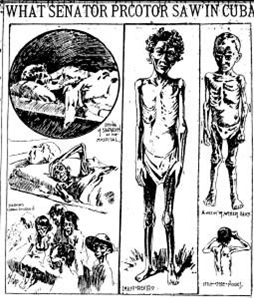

The conflict prompted Spain to impose harsh counter measures. These included “reconcentration” centers where Cuban non-combatants were kept effectively as prisoners amid deplorable and unsanitary conditions.

Content in newspapers other than Hearst’s further undercut the notion “there was no war to cover” in Cuba in early 1897. The New York Sun described the Cuban rebellion as a Spanish-led “war of extermination” and assailed the Spanish leader on the island, Captain-General Valeriano Weyler, as a “savage” who had turned Cuba into “a place of extermination.”

The notion that Hearst vowed in a telegram to Remington to “furnish the war” with Spain is little short of risible. The tale, after all, founders on an irreconcilable internal inconsistency: Why would Hearst pledge to “furnish the war” when war — the island-wide Cuban rebellion against Spanish rule — was the reason he sent Remington and Davis to Cuba in the first place?

The internal inconsistency reduces the “furnish the war” anecdote to an absurdity.

Nonetheless, the anecdote lives on as presumptive evidence that Hearst and his newspapers did bring about the U.S. war with Spain.

But as I wrote in my book, Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies, the newspapers of Hearst and his rival, Joseph Pulitzer, “did not force — [they] could not have forced — the United States into hostilities with Spain over Cuba in 1898. The conflict was, rather, the result of a convergence of forces far beyond the control or direct influence of even … Hearst’s New York Journal.”

Assertions that the so-called “yellow press” of Hearst and Pulitzer brought about the war in 1898 are, I wrote, “exceedingly media-centric, often rest on the selective use of evidence, and tend to ignore more relevant and immediate factors that give rise to armed conflict.”

Foremost among those factors was Spain’s “reconcentration” policy, which caused the deaths from disease and starvation of tens of thousands of Cuban non-combatants.

That humanitarian disaster “inevitably stirred outrage and condemnation in the United States,” I wrote in Yellow Journalism. The desperate conditions in Cuba were in 1897 and early 1898 a frequent topic of reporting in the American press.

Effects of ‘reconcentration’

The newspapers of Hearst and his rivals reported on, but assuredly did not create, the terrible effects of Spain’s “reconcentration” policy.

A leading historian of that period, Ivan Musicant, has correctly observed that the abuses and suffering caused by that policy “did more to bring on the Spanish-American War than anything else the Spanish could have done.”

In the end, the humanitarian crisis on Cuba, and Spain’s inability to resolve the crisis, weighed decisively in the U.S. decision to go to war in 1898.

It was assuredly not a war brought about by newspapers.

Conspicuously absent in argument that Hearst fomented war are explanations about just how the contents of his newspapers were transformed into policy and military action. What was that mechanism?

In truth, there was no such mechanism.

As I pointed out in Yellow Journalism, there is almost no evidence that the content of the yellow press — especially during the decisive weeks following the destruction of the Maine while on a friendly visit to Havana — shaped the thinking or informed the conduct of key officials in the administration of President William McKinley.

“If the yellow press did foment the war,” I wrote, “researchers should be able to find some hint of, some reference to, that influence in the personal papers and the reminiscences of policymakers of the time.

“But neither the diary entries of Cabinet officers nor the contemporaneous private exchanges among American diplomats indicate that the yellow newspapers [of Hearst and Pulitzer] exerted any influence at all. When it was discussed within the McKinley administration, the yellow press was dismissed as a nuisance or scoffed at as a complicating factor.”

No, the news media do not foment war. That’s the reserve of government leaders and policymakers, inept and otherwise.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- The shame of the press

- Getting it excruciatingly wrong about Hearst, Remington, Cuba, and war

- The ‘anniversary’ of a media myth: ‘I’ll furnish the war’

- Hearst, Garrison Keillor, and ‘furnish the war’: Celebrities and media myths

- WaPo book review invokes Hearst myth of ‘furnish the war’

- In myth, a truism: Hearst’s vow ‘will forever live on’

- Obama, journalism history, and ‘folks like Hearst’

- ‘Fake news about fake news’: Enlisting media myths to condemn Trump’s national emergency

- Insidious: Off-hand references signal deep embedding of prominent media myths

- The Post ‘took down a president’? That’s a myth

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ goes on Q-and-A

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

As he had

As he had