In deploring “carefree talk” about pre-emptively bombing Iran’s nuclear installations, Atlantic correspondent James Fallows invokes the mythical tale about William Randolph Hearst’s vow to “furnish the war” with Spain in the late 1890s.

The “furnish the war” anecdote can be just too delicious to resist, as Fallows demonstrates in a rambling commentary posted yesterday at the Atlantic online site.

In it, Fallows writes that “only twice before in my memory, and maybe thrice in American history, has there been as much carefree talk about war and unprovoked strikes as we’ve had concerning Iran in recent months ….

“The twice in my experience were: during the runup to the invasion of Iraq in 2002, and in the ‘bomb ’em back to the stone age’ moments of the early Vietnam era.

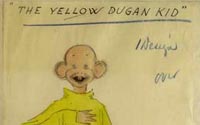

“The time that even I don’t remember was the ‘you furnish the pictures, I’ll furnish the war’ yellow journalism drumbeat before the war with Spain in 1898. This is not good company for today’s fevered discussion to join.”

The line, “you furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war,” was attributed to Hearst more than 110 years ago. But as decades passed, no compelling evidence ever emerged to support or document the tale.

Indeed, it’s often overlooked that Hearst denied making such vow, which he purportedly included in a telegram to the artist Frederic Remington, who was on assignment to Spanish-ruled Cuba in early 1897 for Hearst’s New York Journal.

The telegram to Remington has never surfaced. And Remington apparently never discussed the anecdote, which was recounted first in 1901, in a brief passage in memoir by James Creelman, a blowhard journalist known for frequent exaggeration.

Creelman did not explain how he learned of the “furnish the war” tale which, as I describe in my latest book, Getting It Wrong, is almost surely apocryphal.

Not only does story live on despite the absence of supporting documentation; it lives on despite an irreconcilable internal inconsistency.

That is, it would have been absurd for Hearst to have vowed to “furnish the war” because war — specifically, the Cuban rebellion against Spain’s colonial rule — was the reason he sent Remington to Cuba in the first place.

Cuba in early 1897 was the theater of a nasty war. By then, Spain had dispatched nearly 200,000 troops in a failed attempt to put down the rebellion, which gave rise in 1898 to the Spanish-American War.

Spanish authorities controlled and censured international cable traffic to and from Cuba. They surely would have intercepted — and called attention to — Hearst’s bellicose message, had it been sent. There is little chance the cable would have moved unimpeded from Hearst in New York to Remington in Cuba.

But despite the compelling evidence arrayed against it, the vow attributed to Hearst lives on, and on.

That’s because it has, as I write in Getting It Wrong, “achieved unique status as an adaptable, hardy, all-purpose anecdote, useful in illustrating any number of media sins and shortcomings.

“It has been invoked to illustrate the media’s willingness to compromise impartiality, promote political agendas, and indulge in sensationalism. It has been used, more broadly, to suggest the media’s capacity to inject malign influence into international affairs.”

Which is what Fallows does.

Recent and related:

- Read Chapter One: ‘Furnish the War’

- The ‘anniversary’ of a media myth: ‘I’ll furnish the war’

- Obama, journalism history, and ‘folks like Hearst

- Carl Bernstein, naive and over the top

- Hearst, agenda-setting, and war

- Yellow journalism: A sneer is born

- Two myths and today’s New York Times

- Wrong-headed history: Yellow press stampeded U.S. to war

- Invoking media myths to score points

- Why they get it wrong

- Getting It Wrong goes on Q-and-A