Media Myth Alert today marks its fifth anniversary — an occasion fitting to revisit the top posts since the blog went live on October 31, 2009, with the objectives of calling out the appearance and publication of media myths and helping to promote my 2010 mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong.

Here are the top five of the more than 640 posts at Media Myth Alert. (A separate post today will revisit five other top items posted at Media Myth Alert.)

The top posts all were about prominent topics, all received a fair amount of attention in the blogosphere and beyond, and all were represented disclosures found only at Media Myth Alert.

■ Krakauer quietly retreats from Lynch-source claim (posted November 11, 2011): This post disclosed the walk-back by author Jon Krakauer from claims in his 2009 book that Jim Wilkinson, a former White House official, was the source for the bogus Washington Post report about Jessica Lynch and her battlefield heroics in Iraq in 2003.

Those claims were unattributed in the book — and vigorously denied by Wilkinson, who sought a correction.

Those claims were unattributed in the book — and vigorously denied by Wilkinson, who sought a correction.

When it came, the correction was inserted unobtrusively in a new printing of the paperback edition of Krakauer’s book, Where Men Win Glory.

It read:

“Earlier editions of this book stated that it was Jim Wilkinson ‘who arranged to give the Washington Post exclusive access’ to this leaked intelligence [about Jessica Lynch]. This is incorrect. Wilkinson had nothing to do with the leak.”

I’ve pointed out that the Post’s enduring silence about its sources on the botched story about Lynch has allowed for the emergence not only of bogus allegations such as those about Wilkinson, but of a tenacious false narrative that the Pentagon concocted the tale about Lynch’s derring-do.

The false narrative also has deflected attention from the soldier whose heroics apparently were misattributed to Lynch. He was Sgt. Donald Walters, a cook in Lynch’s unit, which was ambushed in Nasiriyah in southern Iraq in the first days of the Iraq War.

Walters was taken prisoner by Iraqi irregulars, and shot and killed.

■ Calling out the New York Times on ‘napalm girl’ photo error (posted June 3, 2012): The “napalm girl” photograph was one of the most memorable images of the Vietnam War — and remains a source of media myth.

Nick Ut’s Pulitzer-winning image (AP)

The photograph was taken by Nick Ut of the Associated Press on June 8, 1972, and showed terror-stricken Vietnamese children running from an errant aerial napalm attack. The central figure of the image was a naked, 9-year-old girl screaming from her burns.

So powerful was the photograph that it is sometimes said — erroneously — that it hastened an end to the war. Another myth is that the napalm was dropped by U.S. aircraft, a version repeated by the New York Times in May 2012, in an obituary of an Associated Press photo editor, Horst Faas.

The Times’ obituary claimed that the “napalm girl” photograph showed “the aftermath of one of the thousands of bombings in the countryside by American planes.”

That passage suggested U.S. forces were responsible for the napalm attack, and I pointed this out in an email to the Times. I noted that the bombing was a misdirected attack by the South Vietnamese Air Force, as news reports at the time made clear.

An editor for the Times, Peter Keepnews, replied, in what clearly was a contorted attempt to avoid publishing a correction:

“You are correct that the bombing in question was conducted by the South Vietnamese Air Force. However, the obituary referred only to ‘American planes,’ and there does not seem to be any doubt that this plane was American –- a Douglas A-1 Skyraider, to be precise.”

Of course the aircraft’s manufacturer was not at all relevant as to who carried out the attack.

Independent of my efforts, two former senior Associated Press journalists also called on the Times to correct its error about “American planes.”

The Times resisted for weeks before publishing an obscure sort-of correction that embraced Keepnews’ tortured reasoning and stated:

“While the planes that carried out that attack were ‘American planes’ in the sense that they were made in the United States, they were flown by the South Vietnamese Air Force, not by American forces.”

It was, I noted, a muddled and begrudging acknowledgement of error — hardly was in keeping with the declaration by the newspaper’s then-executive editor, Bill Keller, who had asserted in 2011 that “when we get it wrong, we correct ourselves as quickly and forthrightly as possible.”

■ PBS squanders opportunity in tedious War of the Worlds documentary (posted October 29, 2013): The first-ever post at Media Myth Alert was a brief item about Orson Welles’ clever and famous War of the Worlds radio dramatization of October 30, 1938. Welles’ show, which told of a deadly Martian invasion of Earth, supposedly was so terrifying that it pitched tens of thousands of Americans into panic and mass hysteria.

That’s a media myth, one that circulates every year, at the approach of Halloween.

Orson Welles

In 2013, at the 75th anniversary of Welles’ program, PBS revisited The War of the Worlds in a much-anticipated “American Experience” documentary that turned out to be quite a disappointment. PBS managed not only to make The War of the Worlds seem snoozy and tedious; it missed the opportunity to revisit the well-known but much-misunderstood radio program in fresh and revealing ways.

“PBS could have confronted head-on the question of whether the radio show … really did provoke hysteria and mass panic in the United States,” I wrote.

Instead, I added, “The documentary’s makers settled for a turgid program that was far less educational, informative, and inspiring than it could have been.”

The PBS program failed to address the supposed effects of Welles’ radio dramatization in any meaningful way.

And it failed to consider the growing body of scholarship which has impugned the conventional wisdom and has found that The War of the Worlds program sowed neither chaos nor widespread alarm. Instead, listeners in overwhelming numbers recognized the program for what it was: A clever radio show that aired in its scheduled Sunday time slot and featured the not-unfamiliar voice of Welles, the program’s 23-year-old star.

My critique was endorsed by the PBS ombudsman, Michael Getler, who wrote in a column after the documentary was broadcast:

“I find myself in agreement with the judgment of W. Joseph Campbell, the well-known critic and author of ‘Getting It Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism’ who headlined his comment: ‘PBS squanders opportunity to offer “content that educates” in “War of the Worlds” doc.’”

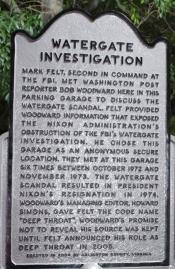

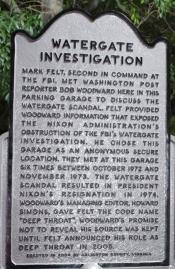

■ ‘Deep Throat’ garage marker errs about Watergate source disclosures (posted August 18, 2011): Few media myths are as enduring as the hero-journalist trope about of Watergate. It holds that the dogged reporting of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein for the Washington Post — guided by Woodward’s clandestine source, code-named “Deep Throat” — exposed the crimes of Watergate and brought down Richard Nixon’s corrupt presidency in 1974.

It’s an easy-to-remember tale that cuts through the considerable complexity of Watergate and, as such, has become the dominant narrative of the scandal.

But it’s a history-lite version of Watergate, a media-centric version that the Post itself has mostly eschewed and dismissed over the years. (Woodward once put it this way: “To say that the press brought down Nixon, that’s horseshit.”)

Marker with the error

A measure of how engrained Watergate’s dominant narrative has become can be seen in the historical marker that went up in August 2011 outside the parking garage in Arlington, Virginia, where Woodward conferred occasionally in 1972 and 1973 with his “Deep Throat” source.

The marker, as I pointed out, errs in describing the information Woodward received from the “Deep Throat” source, who in 2005 revealed himself as W. Mark Felt, formerly the FBI’s second in command.

The marker says:

“Felt provided Woodward information that exposed the Nixon administration’s obstruction of the FBI’s Watergate investigation.”

That’s not so.

Such obstruction-of-justice evidence, had “Deep Throat” offered it to Woodward, would have been so damaging and so explosive that it surely would have forced Richard Nixon to resign the presidency well before he did.

But Felt didn’t have that sort of information — or (less likely) did not share it with Woodward.

The “Deep Throat” garage is to be razed to permit the construction of two commercial and residential towers, the Post reported in June 2014. Interestingly, the Post’s article about the planned demolition repeated nearly verbatim the key portion of the marker’s description, stating:

“Felt … provided Woodward with information that exposed the Nixon administration’s obstruction of the FBI’s Watergate investigation.”

Which is still wrong, even if printed in the newspaper.

■ Suspect Murrow quote pulled at Murrow school (posted February 17, 2011): The online welcome page of the dean of the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication at Washington State University used to feature a quotation attributed to Murrow — a quotation that was only half-true.

Soon after I asked the dean about the provenance of the suspicious quotation, it was taken down.

The quotation read:

“We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. When the loyal opposition dies, I think the soul of America dies with it.”

The first portion of the quote was indeed spoken by Murrow: It was a passage in his mythical 1954 television program that addressed Senator Joseph R. McCarthy’s red-baiting ways.

Not Murrow’s line

The second sentence of the quote — “When the loyal opposition dies, I think the soul of America dies with it” — is apocryphal.

In mid-February 2011, I noted that the full quotation — accompanied by a facsimile of Murrow’s signature — was posted at the welcome page of Dean Lawrence Pintak of Murrow College at Washington State, Murrow’s alma mater.

I asked the dean what knew about the quote’s first appearance, noting that I had consulted, among other sources, a database of historical newspapers which contained no articles quoting the “loyal opposition” passage.

Pintak, who said he believed the Web page containing the suspect quote had been developed before his arrival at Washington State in 2009, referred my inquiry to an instructor on his faculty who, a few hours later, sent an email to the dean and me, stating:

“While [the ‘loyal opposition’ quotation] seems to reflect the Murrow spirit, the lack of evidence that he phrased it that way is indeed suspicious.”

He added: “I feel the evidence says no, Murrow did not say this.”

By day’s end, the suspect quote had been pulled from the welcome page. Just the authentic portion — “We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty” — remained posted there.

The bogus Murrow quote about “the loyal opposition” has popped up before.

For example, in a speech in 2006 about Iraq, Harry Reid, now the U.S. Senate majority leader, invoked the passage — and claimed Murrow was its author.

WJC

Other memorable posts at Media Myth Alert:

So it was the other day when the Salt Lake Tribune

So it was the other day when the Salt Lake Tribune

Late October makes for memorable times in

Late October makes for memorable times in