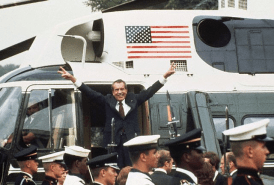

Nixon’s resignation: Not the media’s doing

Coinciding with the closing days of this year’s wretched election campaign has been the appearance of prominent media myths about the Watergate scandal and the first televised debate in 1960 between major party presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon.

The myths, respectively, have it that the dogged reporting by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered the crimes that brought down Nixon’s presidency in 1974, and that television viewers and radio listeners reached sharply different conclusions about the debate outcome, signaling that image trumps substance.

Both myths have become well-entrenched dominant narratives over the years and they tend to be blithely invoked by contemporary journalists.

Take, for example, the lead paragraph of an Atlantic article posted a couple of days ago; it flatly declared:

“The Watergate Scandal was a high point of American journalism. Two dedicated young reporters from The Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, brought down President Richard Nixon for his role in the coverup of the 1972 attempted break in of the Democratic Party headquarters by Republican operatives.”

In an otherwise thoughtful analysis posted today about the new media’s failings in this year presidential campaign, David Zurawik of the Baltimore Sun invoked the Watergate myth, stating:

“And how was Nixon forced to resign if not through the old-school, legacy standards of dogged investigative journalism?”

Zurawik referred to Bernstein as “[o]ne of the journalistic elders who brought Nixon down.”

As I discuss in my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong — a second edition of which recently was published — the Washington Post was at best a marginal contributor to Nixon’s fall.

As I discuss in my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong — a second edition of which recently was published — the Washington Post was at best a marginal contributor to Nixon’s fall.

Unraveling a scandal of Watergate’s dimensions, I write in Getting It Wrong, “required the collective if not always the coordinated forces of special prosecutors, federal judges, both houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, as well as the Justice Department and the FBI.

“Even then,” I add, “Nixon likely would have served out his term if not for the audiotape recordings he secretly made of most conversations in the Oval Office of the White House. Only when compelled by the Supreme Court did Nixon surrender those recordings, which captured him plotting the cover-up” of the burglary of Democratic National Committee headquarters in June 1972, the seminal crime of Watergate.

Most senior figures at the Post during the Watergate period — including Woodward, Executive Editor Ben Bradlee, and Publisher Katharine Graham — scoffed at claims the newspaper’s reporting toppled Nixon.

Woodward, for example, told American Journalism Review in 2004:

“To say the press brought down Nixon, that’s horse shit.”

The myth about the 1960 debate was invoked almost casually in a column the other day in Raleigh’s News & Observer newspaper. The writer asserted:

“The televised debates were said to give the nod to the telegenic Kennedy, while radio listeners believed Nixon the victor.”

But as I point out in the new edition of Getting It Wrong, the notion of viewer-listener disagreement is “a dubious bit of political lore” often cited as presumptive “evidence of the power of television images and the triumph of image over substance.”

The myth of viewer-listener disagreement, I also point out, “was utterly demolished” nearly 30 years ago in a scholarly journal article by David L. Vancil and Sue D. Pendell.

Vancil and Pendell, writing in Central States Speech Journal, reviewed and dissected the few published surveys that hinted at a viewer-listener disconnect in the Kennedy-Nixon debate of September 26, 1960.

Central to the claim that radio audiences believed Nixon won the debate was a survey conducted by Sindlinger & Company. The Sindlinger survey indicated that radio listeners thought Nixon had prevailed in the debate, by a margin of 2-to-1.

Vancil and Pendell pointed out that the Sindlinger survey included more than 2,100 respondents — just 282 of whom said they had listened on radio. Of that number, 178 (or fewer than four people per state) “expressed an opinion on the debate winner,” they wrote. The sub-sample was decidedly too small few and unrepresentative to permit meaningful generalizations or conclusions, Vancil and Pendell noted.

Not only was it unrepresentative, the sub-sample failed to identify from where the radio listeners were drawn. “A location bias in the radio sample,” Vancil and Pendell wrote, “could have caused dramatic effects on the selection of a debate winner. A rural bias, quite possible because of the relatively limited access of rural areas to television in 1960, would have favored Nixon.”

Those and other defects render the Sindlinger survey meaningless in offering insights to reactions of radio listeners.

In the second edition of Getting It Wrong, I seek to build upon the work of Vancil and Pendell, offering contemporaneous evidence from a detailed review of debate-related content in three dozen large-city U.S. daily newspapers. Examining the news reports and commentaries published in those newspapers in the debate’s immediate aftermath turned up no evidence to support the notion of viewer-listener disagreement, I write, adding:

“None of the scores of newspaper articles, editorials, and commentaries [examined] made specific reference” to the supposed phenomenon of viewer-listener disagreement. “Leading American newspapers in late September 1960 spoke of nothing that suggested or intimated pervasive differences in how television viewers and radio listeners reacted to the landmark debate.”

And they were well-positioned to have done so, given the keen interest in, and close reporting about, the first debate between major party candidates.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- Memorable late October: A new edition of ‘Getting It Wrong,’ and more

- Trump, Nixon, and the ‘secret plan’ media myth

- USA Today invokes Kennedy-Nixon debate myth

- CNN launches ‘Race for White House’ series with hoary myth about 1960 debate

- 1960 myth ricochets around media in advance of Obama-Romney debate

- Gushing about ‘All the President’s Men,’ the movie, and ignoring the myths it propelled

- The hero-journalist trope: Watergate’s go-to mythical narrative

- Recalling George Romney’s ‘brainwashing’ — and Gene McCarthy’s ‘light rinse’ retort

- WSJ columnist, trying to explain Trump, trips over Cronkite-Johnson myth

- ‘A debunker’s work is never done’

- Check out The 1995 Blog

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

But Trump’s superficiality hasn’t stopped

But Trump’s superficiality hasn’t stopped