To say that prominent media myths, those dubious tall tales about the media and the exploits of journalists, are immune from debunking is to confirm a truism.

Shield him from debates?

Some media-centric tall tales are just too good to die away.

These include the heroic trope that two young, dogged reporters for the Washington Post brought down Richard Nixon’s corrupt presidency in the Watergate scandal. They include the notion that a pessimistic, on-air assessment by anchorman Walter Cronkite about the Vietnam War in 1968 turned American public opinion against the conflict.

And they include the exaggerated narrative of the first presidential debate in 1960 between Nixon and John F. Kennedy, that the former “won” the debate among radio listeners but, because he perspired noticeably and looked wan, “lost” among television viewers.

The myth of viewer-listener disagreement was thoroughly and impressively demolished 33 years ago and yet it lives on; it lives on at the New York Times, which unreservedly offered up the myth in an essay published yesterday.

The essay proposed an end to the presidential debates — a fixture in the U.S. political landscape since 1976 — because “have never made sense as a test for presidential leadership.” The author, veteran Washington journalist Elizabeth Drew who was on a debate panel 44 years ago, has made such an argument before.

But the essay’s publication yesterday also looked like prospective justification for shielding gaffe-prone Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, from confronting President Donald Trump in three 90-minute debates during the unfolding campaign. Biden’s fumbling, sometimes-bizarre statements may not serve him well in such encounters. (Of course, as Drew has written on other occasions, Trump’s isn’t necessarily an effective or well-prepared debater.)

What most interested Media Myth Alert, though, was Drew’s invoking the myth of viewer-listener disagreement.

“Perhaps the most substantive televised debate of all,” she wrote, “was the first one, between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, which Nixon was considered to have won on substance on the radio, while the cooler and more appealing Kennedy won on television.”

Nixon “won on substance on the radio” while “Kennedy won on television.”

Uh-huh.

As I noted in the second edition of my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong, “the myth of viewer-listener disagreement [is] one of the most resilient, popular, and delectable memes about the media and American politics. Despite a feeble base of supporting documentation, it is a robust trope” that rests more on assertion, and repetition, than on evidence.

Had television and radio audiences differed sharply about the debate’s outcome, journalists in 1960 were well-positioned to detect and report on such disparate perceptions — especially in the immediate aftermath of the first Kennedy-Nixon encounter, when interest in the debate and its novelty ran high.

But of the scores of newspaper articles, editorials, and commentaries I examined in my research about the Nixon-Kennedy debate, none made specific reference to such an audience effect. Even oblique hints of viewer-listener disagreement were few, vague, and fleeting.

Moreover, I wrote in Getting It Wrong, “there was no unanimity among newspaper columnists and editorial writers about Nixon’s appearance” on television during the first debate, noting:

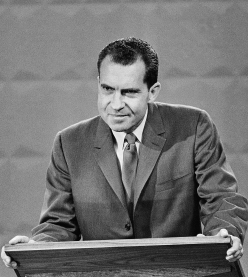

Not everyone thought Nixon looked awful (AP photo)

“Not all analysts in late September 1960 thought Nixon’s performance was dreadful — or that Kennedy was necessarily all that appealing and rested.”

An after-debate editorial in the Washington Post declared, for example:

“Of the two performances, Mr. Nixon’s was probably the smoother. He is an accomplished debater with a professional polish, and he managed to convey a slightly patronizing air of a master instructing a pupil.”

Saul Pett, then a prominent writer for the Associated Press, assigned Nixon high marks for cordiality. “On general folksiness both before and during the debate,” Pett wrote, “my scorecard showed Nixon ahead at least 8 to 1. … He smiled more often and more broadly, especially at the start and close of a remark. Kennedy only allowed himself the luxury of a quarter-smile now and then.”

Nixon’s tactics during the debate, rather than how he looked on television, probably were more damaging.

I note in Getting It Wrong that Nixon “committed then the elementary mistake of arguing on his opponent’s terms — of seeming to concur rather than seeking the initiative. Nixon projected a ‘me-too’ sentiment from the start, in answering Kennedy who had spoken first.”

Surprisingly, Nixon in his opening statement declared that he agreed with much of what Kennedy had just said.

The dearth of evidence that Nixon’s appearance was decisive to the debate’s outcome was underscored in a journal article in 1987 by scholars David Vancil and Sue D. Pendell. It remains a fine example of thorough, evidence-based debunking.

Writing in Central States Speech Journal, Vancil and Pendell pointed out that no public opinion surveys conducted in the debate’s immediate aftermath were aimed specifically at measuring views or reactions of radio audiences.

Vancil and Pendell also noted: “Even if viewers disliked Nixon’s physical appearance, the relative importance of this factor is a matter of conjecture.” To infer “that appearance problems caused Nixon’s loss, or Kennedy’s victory,” they added, “is classic post hoc fallacy.”

Quite so.

Flaws in Drew’s commentary about the presidential debates went beyond mentioning the hoary media myth (which she also invoked in her 2007 book about Nixon). An editorial in the Wall Street Journal referred specifically to Drew’s commentary, asserting:

“What a terrible year to make this argument. The pandemic has put the usual political rallies on hold, so fewer voters will see the candidates in the flesh. The conventions will be largely online. Press aides will shape the news coverage by picking friendly interviewers. … Also, Mr. Biden would take office at age 78, becoming the oldest President in history on Day 1. Mr. Trump is all but calling him senile, and Mr. Biden’s verbal stumbles and memory lapses were obvious in the Democratic primaries.”

Modifying the format of one-on-one presidential debates would be far preferable to scrapping them, which would look awfully suspicious.

And cowardly.

More from Media Myth Alert

- No, ‘Politico’: Viewer-listener disagreement is a myth of JFK-Nixon debate

- No, Politico: WaPo didn’t bring down Nixon

- Memorable late October: A new edition of ‘Getting It Wrong,’ and more

- USAToday invokes Kennedy-Nixon debate myth

- Media myths of Watergate, ’60 debate circulate as campaign enters closing days

- Who won ’60 debate? Can’t say: Didn’t see it on TV

- It’s like 1948 all over again for American media

- WaPo, Helen Thomas, and Nixon’s ‘secret plan’

- Smug MSNBC guest invokes Nixon’s mythical ‘secret plan’ on Vietnam

- NYTimes ignores senior former AP journalists seeking correction on ‘napalm girl’ context

- A sort-of correction from the NYTimes

- Of media myths and false lessons abroad: Biden’s Moscow gaffe

- Media myths, the ‘comfort food’ of journalism

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ goes on Q-and-A

As I discuss in my media-

As I discuss in my media- Late October makes for memorable times in

Late October makes for memorable times in

“Even the oblique hints of viewer-listener disagreement were vague and few,” I write, adding:

“Even the oblique hints of viewer-listener disagreement were vague and few,” I write, adding: