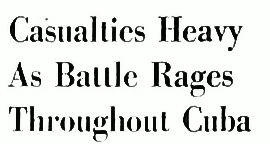

This is a twist: The Pakistan military may be facing its “Cronkite Moment” in the fallout from the stunning Navy SEALs’ raid that took down terror leader Osama bin Laden.

That, at least, is what ABC News Radio reported yesterday, noting recent on-air criticism by Kamran Khan, a leading Pakistan television journalist whom it characterized as “typically pro-military.”

Khan said last week of Pakistan:

”We have become the biggest haven of terrorism in the world and we have failed to stop it.”

Khan’s criticism, according to ABC, may represent “the Pakistani military’s ‘Walter Cronkite moment,’ akin to when the United States’ most popular television anchor declared in 1968 that Vietnam was unwinnable — after which Lyndon Johnson said, ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.'”

As is discussed in my latest book, Getting It Wrong, the purported “Cronkite Moment” a prominent and hardy media-driven myth — a dubious tale about the news media masquerading as factual.

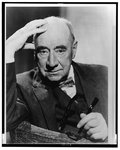

ABC’s claim notwithstanding, Cronkite did not declare the Vietnam War “unwinnable.” At the close of a special report televised on February 27, 1968, the CBS News anchorman said the U.S. military effort in Vietnam was “mired in stalemate.”

And that was a wholly unremarkable and unoriginal observation. The New York Times had for months been using “stalemate” to characterize the war effort.

I further note in Getting It Wrong that “a close reading of the transcript of Cronkite’s closing remarks reveals how hedged and cautious they really were. … Cronkite held open the possibility that the U.S. military efforts might still force the North Vietnamese to the bargaining table and suggested the U.S. forces be given a few months more to press the fight in Vietnam.”

So, no, Cronkite didn’t declare the war “unwinnable.”

Nor is there any documented evidence that President Lyndon Johnson had a powerful, visceral reaction to Cronkite’s fairly pedestrian commentary.

Johnson, as I discuss in Getting It Wrong, did not see the Cronkite special report when it aired.

Johnson at the time was in Austin, Texas, on the campus of the University of Texas, making light-hearted remarks at the 51st birthday party of a longtime political ally, Governor John Connally.

About the time Cronkite was intoning his “mired in stalemate” assessment, Johnson wasn’t lamenting the supposed loss of the anchorman’s support. He wasn’t lamenting the failings of his Vietnam policy.

Johnson was saying: “Today you are 51, John. That is the magic number that every man of politics prays for — a simple majority.”

Now, that wasn’t the finest joke ever told by an American president. But it clearly demonstrated that Johnson wasn’t fretting about Cronkite that night.

In the days that followed the purported “Cronkite Moment,” Johnson remained forceful and adamant in public statements about the war effort in Vietnam. He was not despairing.

Indeed, just three days after Cronkite’s special report aired, Johnson took to the podium at a testimonial dinner in Texas and vowed that the United States would “not cut and run” from Vietnam.

“We’re not going to be Quislings,” the president said, invoking the surname of a Norwegian politician who helped the Nazis during World War II. “And we’re not going to be appeasers….”

Clearly, the presumptive “Cronkite Moment” was no epiphany for Lyndon Johnson.

Recent and related:

- Lynch heroics not ‘the Pentagon’s story’; it was WaPo’s

- ‘Mired in stalemate’? How unoriginal of Cronkite

- ‘Cronkite Moment’ makes ‘Best of the Web’

- Fact-checking ‘Mother Jones’: A rare two-fer

- Newsman ‘tells a simple truth,’ changes history: Sure he did

- On Cronkite, Jon Stewart and ‘the most trusted’ man

- ‘Lyndon Johnson went berserk’? Not because of Cronkite

- LBJ’s Vietnam epiphany wasn’t Cronkite’s show

- Two myths and today’s New York Times

- Invoking media myths to score points

- Not off the hook with ‘reportedly’

- ‘Commentary’ reviews ‘Getting It Wrong’