The trade journal Editor & Publisher once was something of a must-read periodical in the news business. It was never much of a crusading magazine, but its announcements about hirings and departures, as well as its classified ads, were closely watched by professional journalists.

E&P, as it’s called, traces its pedigree to the late 19th century but is hardly much of a force these days. It nearly went out of business 12 years or so ago and more recently was sold to a company led by media consultant Michael Blinder.

E&P, as it’s called, traces its pedigree to the late 19th century but is hardly much of a force these days. It nearly went out of business 12 years or so ago and more recently was sold to a company led by media consultant Michael Blinder.

He is E&P’s publisher and in a column posted this week at the publication’s website, Blinder blamed the news media for exacerbating political divisions in the country. In a passage of particular interest to Media Myth Alert, Blinder wrote:

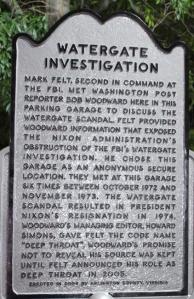

“I ask you, in today’s media ecosystem, could Edward R. Murrow have really brought that critical ‘truth to power’ that took down Senator Joe McCarthy? Or would Richard Nixon have had to resign over his many documented cover-ups revealed by Woodward and Bernstein? The answer is ‘no!'”

The answer indeed is “no,” because broadcast legend Murrow of CBS did not take down McCarthy. And Nixon did not resign because of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s reporting for the Washington Post.

Those claims are hoary, media-driven myths — tales about and/or by the news media that are widely believed and often retold but which, under scrutiny, dissolve as apocryphal or highly exaggerated.

The myths of Murrow-McCarthy and of Watergate are still widely believed despite having been thoroughly debunked.

And not only debunked: they’ve been dismissed or scoffed at by journalists who figured centrally in the respective tales.

As I wrote in my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong, after his famous See It Now television program about McCarthy on March 9, 1954, “Murrow said he recognized his accomplishments were modest, that at best he had reinforced what others had long said” about the red-baiting senator from Wisconsin.

McCarthy: red-baiting senator

The television critic for the New York Post, Jay Nelson Tuck, wrote that Murrow felt “almost a little shame faced at being saluted for his courage in the McCarthy matter. He said he had said nothing that … anyone might not have said without a raised eyebrow only a few years ago.”

Not only that, but as I wrote in Getting It Wrong, “Murrow in fact was very late in confronting McCarthy, that he did so only after other journalists [such as muckraking columnist Drew Pearson] had challenged the senator and his tactics” long before March 1954.

Additionally, Murrow’s producer and collaborator, Fred W. Friendly, scoffed at the notion that Murrow’s program was pivotal or decisive, writing in his memoir: “To say that the Murrow broadcast of March 9, 1954, was the decisive blow against Senator McCarthy’s power is as inaccurate as it is to say that Joseph R. McCarthy … single-handedly gave birth to McCarthyism.”

Even more adamant, perhaps, was Bob Woodward’s dismissing the notion his reporting brought down Nixon’s corrupt presidency.

Woodward declared in an interview in 2004:

“To say that the press brought down Nixon, that’s horseshit.”

Woodward’s appraisal, however inelegant, is on-target. He and Bernstein did not topple Nixon.

Nor did they reveal, as Blinder writes, Nixon’s coverup of the crimes of Watergate, which began with a botched burglary in June 1972 at headquarters of the Democratic National Committee.

As Columbia Journalism Review pointed out in 1973, in a lengthy and hagiographic account about Woodward and Bernstein:

“The Post did not have the whole story [of Watergate], by any means. It had a piece of it. Woodward and Bernstein, for understandable reasons, completely missed perhaps the most insidious acts of all — the story of the coverup and the payment of money to the Watergate defendants to buy their silence.”

They “completely missed” the coverup.

The journalism review quoted Woodward as saying this about the coverup and hush money payments: “‘It was too high. It was held too close. Too few people knew. We couldn’t get that high.’”

As I discussed in Getting It Wrong, the New York Times “was the first news organization to report the payment of hush money to the Watergate burglars, a pivotal disclosure that made clear that efforts were under way to conceal the roles of others in the scandal.” I quoted a passage in a book by John Dean, Nixon’s former counsel, as saying the Times‘ report about hush-money payments “hit home! It had everyone concerned and folks in the White House and at the reelection committee were on the wall.”

Unequivocal evidence of Nixon’s guilty role in coverup wasn’t revealed until August 1974, with disclosure of the so-called “smoking gun” audiotape, the release of which had been ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The tape’s content sealed Nixon’s fate.

On the “smoking gun” tape — one of many Nixon had secretly recorded at the White House and elsewhere — the president can be heard approving a plan to use the CIA to divert the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in.

The notion that the reporting of Woodward and Bernstein brought down Nixon may be cheering and reassuring to contemporary journalists. But it is a misleading interpretation that minimizes the more powerful and decisive forces — such as the Supreme Court — that were crucial to Watergate’s unraveling and to Nixon’s resignation in the summer of 1974.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- On media myths and hallowed moments of exaggerated importance

- The hero-journalist myth of Watergate

- More Watergate mythologizing: Woodward, Bernstein ‘let facts speak’ and Nixon fell

- The Nixon tapes: A pivotal Watergate story that WaPo missed

- Murrow, McCarthy and ‘the guts to say enough is enough’

- Media too scared to challenge Joe McCarthy? Hardly

- Murrow the brave? Not in McCarthy days

- Only Murrow had the bona fides? Nonsense

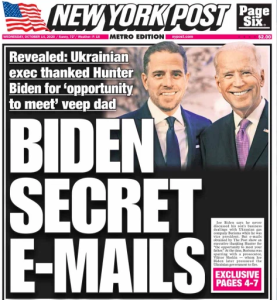

- Two myths and today’s New York Times

- Media history with Olbermann: Wrong and wrong

- ‘Persuasive and entertaining’: WSJ reviews ‘Getting It Wrong’

“Not so much anymore.”

“Not so much anymore.”

The producers most likely

The producers most likely