“Yellow journalism” is a disparaging epithet often invoked in journalism, even though its derivation is little known.

This is the back story to a sneer that trips easily off the tongue with scorn and condescension.

The first verified use of the term was 115 years ago today, when “yellow journalism” appeared in the old New York Press.

The phrase “the Yellow Journalism” appeared in a small headline on the Press’ editorial page on January 31, 1897. The phrase also appeared that day in the newspaper;s editorial page gossip column, “On the Tip of the Tongue.”

“Yellow journalism” was quickly embraced in American newspapering, as a way to disparage and denigrate the freewheeling practices of William Randolph Hearst and his New York Journal as well as Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World.

Within weeks of the first use of the term, references to “yellow journalism” had appeared in newspapers in Providence, Richmond, and San Francisco.

In the 115 years since then, “yellow journalism” has turned into a derisive if vague shorthand for denouncing sensationalism and journalistic misconduct of all kinds.

“It is,” I wrote in my 2001 book, Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies, “an evocative term that has been diffused internationally, in contexts as diverse as Greece and Nigeria, as Israel and India.”

I also noted that yellow journalism emerged in “a lusty, fiercely competitive, and intolerant time, when newspapers routinely traded brickbats and insults” and even threats.

Just how Wardman and the Press came up with “yellow journalism” is not clear.

The newspaper’s own, brief discussion of the term’s derivation was decidedly unrevealing. “We called them Yellow because they are Yellow,” the Press said in 1898 in a comment about the Journal and the World.

In the 1890s, the color yellow sometimes was associated with depraved literature, which may have been an inspiration to Wardman, an austere figure largely lost to New York newspaper history. (The New York Times said in 1923 in its obituary of Wardman: “Like many another anonymous worker in journalism, his name was not often conspicuously before the public, and he was content to sink his personality in that of the papers which he served.”)

Wardman, who earned a bachelor’s degree in three years at Harvard University, once was described as showing “Calvinistic ancestry in every line of his face.” He did little to conceal his contempt for Hearst and Hearst’s flamboyant style of journalism.

Disdain routinely spilled into the columns of the Press, of which Wardman became editor in chief in 1896 at the age of 31. (The Press ceased publication in 1916.)

The Press took to taunting Hearst, Hearst’s mother, and Hearst’s support for Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election. Hearst’s Journal was virtually alone among New York newspapers in supporting Bryan’s “free silver” candidacy.

The Press taunted Hearst, then 34, as a mama’s boy and “little Willie.” It referred to the Journal as “our silverite, or silver-wrong, contemporary.”

The Press also experimented with pithy if stilted turns of phrase to denounce “new journalism,” Hearst’s preferred term to characterize his style of newspapering.

“The ‘new journalism,’” the Press said in early January 1897 “continues to think up a varied assortment of new lies.”

Later in the month, the Press asked in a single-line editorial comment:

“Why not call it nude journalism?”

It clearly was a play on “new journalism” and was meant to suggest the absence of “even the veneer of decency.”

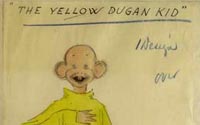

It wasn’t long before Wardman and the Press seized upon the phrase “yellow-kid journalism,” which evoked the Hearst-Pulitzer rivalry over a popular cartoon character known as the “Yellow Kid.” Both the Journal and the World at the time were publishing versions of the kid.

At the end of January 1897, the phrase “yellow-kid journalism” was modified to “the Yellow Journalism,” and the sneer was born.

Wardman turned often to this delicious pejorative, invoking it in a number of brief editorial comments such as:

“The Yellow Journalism is now so overripe that the little insects which light upon it quickly turn yellow, too.”

The diffusion of “yellow journalism” was confirmed when Hearst’s Journal embraced the term in mid-May 1898, during the Spanish-American War. With typical immodesty, it declared:

“… the sun in heaven is yellow—the sun which is to this earth what the Journal is to American journalism.”

Adapted from an essay posted in 2010 at Media Myth Alert.

Recent and related:

- Sketches published 115 years ago undercut a tenacious media myth

- Yellow journalism ‘brought about the Spanish-American War’? But how?

- Hearst pushed country into war? But how?

- 60 years after his death, media myth towers around Hearst

- Getting it right about ‘yellow journalism’

- Hearst and war: An editor misreads history

- Hearst, war, and the international appeal of media myths

- Obama, journalism history, and ‘folks like Hearst’

- More than merely sensational

- 1897 flashback: Committing ‘jailingbreaking journalism’

- NYT’s Keller and the dearth of viewpoint diversity in newsrooms

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism