Media Myth Alert called attention in 2016 to the appearance of prominent media-driven myths, including cases discussed in a new, expanded edition of Getting It Wrong: Debunking the Greatest Myths in American Journalism, which was published in October.

called attention in 2016 to the appearance of prominent media-driven myths, including cases discussed in a new, expanded edition of Getting It Wrong: Debunking the Greatest Myths in American Journalism, which was published in October.

Here is a rundown of Media Myth Alert’s five top posts of the year, followed by references to other notable mythbusting writeups of 2016.

■ ‘Scorched by American napalm’: The media myth of ‘Napalm Girl’ endures (posted August 22): The new edition of Getting It Wrong includes three new chapters — one of which debunks the myths associated with the “Napalm Girl” photograph, which showed a cluster of terrorized Vietnamese children fleeing an errant napalm attack at Trang Bang, a village northwest of Saigon.

Most prominent among the myths is that the napalm was dropped by U.S. forces — a claim the Los Angeles Times repeated in a profile in August about Nick Ut of the Associated Press, who took the photograph on June 8, 1972. The profile described how “Ut stood on a road in a village just outside of Saigon when he spotted the girl — naked, scorched by American napalm and screaming as she ran.”

Shortly after Media Myth Alert called attention to the erroneous reference to “American napalm,” the Times quietly removed the modifier “American” — but without appending a correction.

As I point out in Getting It Wrong, the myth of American culpability in the attack at Trang Bang has been invoked often over the years.

The notion of American responsibility for the napalm attack took hold in the months afterward, propelled by George McGovern, the hapless Democratic candidate for president in 1972. McGovern referred to the image during his campaign, saying the napalm had been “dropped in the name of America.”

That metaphoric claim was “plainly overstated,” I write, adding:

“The napalm was dropped on civilians ‘not in the name of America’ but in an errant attempt by South Vietnamese forces to roust North Vietnamese troops from bunkers dug at the outskirts of the village. That is quite clear from contemporaneous news reports.”

The Los Angeles Times placed the “napalm girl” photograph on its front page of June 9, 1972 (see nearby); the caption made clear that the napalm had been “dropped accidentally by South Vietnamese planes.”

So why does it matter to debunk the myths of the “Napalm Girl”?

The reasons are several.

“Excising the myths … allows the image to be regarded and assessed more fairly, on its own terms,” I write in Getting It Wrong. “Debunking the myths of ‘Napalm Girl’ does nothing to diminish the photograph’s exceptionality. But removing the barnacles of myth effectively frees the photograph from association with feats and effects that are quite implausible.” That’s a reference to other myths of the “Napalm Girl,” that the image was so powerful that it swung public opinion against the war and hastened an end to the conflict.

But like the notion of American culpability in the errant attack, those claims are distortions and untrue.

■ NYTimes’ Castro obit gets it wrong about NYTimes’ Bay of Pigs coverage (posted November 26): Fidel Castro died in late November and the New York Times in a lengthy obituary called the brutal Cuban dictator “a towering international figure.” The Times obituary also invoked a persistent media myth about its own coverage of the run-up to the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

The obituary said that the Times, “at the request of the Kennedy administration, withheld some” details of the invasion plans, “including information that an attack was imminent.”

But as I describe in Getting It Wrong, the notion that the administration of President John F. Kennedy “asked or persuaded the Times to suppress, hold back, or dilute any of its reports about the impending Bay of Pigs invasion is utter fancy.”

What I call the “New York Times-Bay of Pigs suppression myth” centers around the editing of a single article by Tad Szulc, a veteran foreign correspondent for the Times. Eleven days before the invasion, Szulc reported from Miami that an assault, organized by the CIA, was imminent.

Editors at the Times removed references to imminence and to the CIA.

“Imminent,” they reasoned, was more prediction than fact.

And the then-managing editor, Turner Catledge, later wrote that he “was hesitant to specify the CIA when we might not be able to document the charge.” So references to CIA were replaced with the more nebulous term “U.S. officials.”

Both decisions were certainly justifiable. And Szulc’s story appeared April 7, 1961, above-the-fold on the Times front page (see image nearby).

As the veteran Timesman Harrison Salisbury wrote in Without Fear or Favor, his insider’s account of the Times:

As the veteran Timesman Harrison Salisbury wrote in Without Fear or Favor, his insider’s account of the Times:

“The government in April 1961 did not … know that The Times was going to publish the Szulc story, although it was aware that The Times and other newsmen were probing in Miami. … The action which The Times took [in editing Szulc’s report] was on its own responsibility,” the result of internal discussions and deliberations that are recognizable to anyone familiar with the give-and-take of newsroom decision-making.

What’s rarely recognized or considered in asserting the suppression myth is that the Times’ reporting about the runup to the invasion was hardly confined to Szulc’s article.

Indeed, the Times and other news outlets “kept expanding the realm of what was publicly known about a coming assault against Castro,” I write, noting that the newspaper “continued to cover and comment on invasion preparations until the Cuban exiles hit the beaches at the Bay of Pigs” on April 17, 1961.

Suppressed the coverage was not.

■ Smug MSNBC guest invokes Nixon’s mythical ‘secret plan’ on Vietnam (posted May 3): Donald Trump’s shaky grasp of foreign policy invited his foes to hammer away at his views — and one of them, left-wing activist Phyllis Bennis, turned to a tenacious media myth to bash the Republican candidate.

Bennis did so in late April, in an appearance on the MSNBC program, The Last Word with Lawrence O’Donnell.

Trump during his campaign vowed to eradicate ISIS, the radical Islamic State, but wasn’t specific about how that would be accomplished.

Bennis, showing unconcealed smugness, declared on the MSNBC show that Trump’s reference to ISIS “was very reminiscent of Nixon’s call when he was running for president [in 1968] and said, ‘I have a secret plan to end the war.’ The secret plan of course turned out to be escalation.”

In fact, the “secret plan” to end the Vietnam War was a campaign pledge Nixon never made.

He didn’t campaign for the presidency by espousing or touting or proclaiming a “secret plan” on Vietnam.

That much is clear from the search results of a full-text database of leading U.S. newspapers in 1968, including the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Baltimore Sun, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune. The search terms “Nixon” and “secret plan” returned no articles during the period from January 1, 1967, to January 1, 1969, in which Nixon was quoted as saying he had a “secret plan” for Vietnam. (The search period included all of Nixon’s presidential campaign and its immediate aftermath.)

Surely, if Nixon had campaigned on a “secret plan” in 1968, as Bennis so snootily claimed, the country’s leading newspapers would have publicized it.

Nixon did publicly confront the notion he had a “secret plan” for Vietnam. In an article published March 28, 1968, in the Los Angeles Times, he was quoted as saying he had “no gimmicks or secret plans” for Vietnam.

Nixon also said on that occasion:

“If I had any way to end the war, I would pass it on to President [Lyndon] Johnson.” (Nixon’s remarks were made just a few days before Johnson announced he would not seek reelection.)

Nixon may or may not have had a “secret plan” in mind in 1968. But such a claim was not a feature of his campaign.

■ No, ‘Politico’ — Hearst didn’t vow to ‘furnish the war’ (posted December 18): The vow attributed to William Randolph Hearst to “furnish the war” with Spain in the late 19th century is a zombie-like bogus quote: Despite thorough and repeated debunking, it never dies.

Confirmation of its zombie-like character was in effect offered by Politico in December, in an essay about the “long and brutal history of fake news.” Politico cited, as if it were true, the fake tale of Hearst’s “furnish the war” vow.

As I wrote in a Media Myth Alert post about Politico‘s use of the mythical quote:

“Hearst’s vow, supposedly contained in an exchanged of telegrams with the artist Frederick Remington, is one of the most tenacious of all media myths, those dubious tales about and/or by the news media that are widely believed and often retold but which, under scrutiny, dissolve as apocryphal. They can be thought of as prominent cases of ‘fake news‘ that have masqueraded as fact for years.”

The tale, I write in Getting It Wrong, “lives on despite a nearly complete absence of supporting documentation.

“It lives on even though telegrams supposedly exchanged by Remington and Hearst have never turned up. It lives on even though Hearst denied ever sending such a message.”

And it lives on despite what I call “an irreconcilable internal inconsistency.” That is, it would have been illogical for Hearst to have sent a message vowing to “furnish the war” because war — Cuba’s rebellion against Spanish colonial rule, begun in 1895 — was the very reason Hearst assigned Remington to Cuba at the end of 1896.

Debunking the Hearstian vow is the subject of Chapter One in Getting It Wrong; the chapter is accessible here.

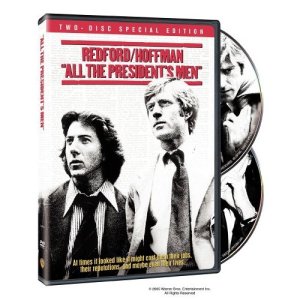

■ NYTimes invokes Watergate myth in writeup about journalists and movies (posted January 3): Watergate’s mythical dominant narrative has it that dogged reporting by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post exposed the crimes that toppled Richard Nixon’s corrupt presidency in 1974.

The dominant narrative (the heroic-journalist trope, I call it) emerged long ago, and Hollywood — specifically, the cinematic version of Woodward and Bernstein’s book about their Watergate reporting — is an important reason why.

The movie, All the President’s Men, was released to critical acclaim 40 years ago and unabashedly promotes the heroic-journalist interpretation, that Woodward and Bernstein were central to unraveling Watergate and bringing down Nixon.

I point out in Getting It Wrong that All the President’s Men “allows no other interpretation: It was the work Woodward and Bernstein that set in motion far-reaching effects that brought about the first-ever resignation of a U.S. president. And it is a message that has endured” — as was suggested by a New York Times in an article in early January.

The article, which appeared beneath the headline “Journalism Catches Hollywood’s Eye,” embraced the heroic-journalist myth in referring to “the investigation by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein that led to Richard M. Nixon’s resignation.”

Their reporting had no such effect, however much All the President’s Men encouraged that simple notion.

I point out in Getting It Wrong that rolling up a scandal of Watergate’s dimensions “required the collective if not always the coordinated forces of special prosecutors, federal judges, both houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, as well as the Justice Department and the FBI.

“Even then, Nixon likely would have served out his term if not for the audiotape recordings he secretly made of most conversations in the Oval Office of the White House. Only when compelled by the Supreme Court did Nixon surrender those recordings, which captured him plotting the cover-up” of the burglary in June 1972 that was Watergate’s seminal crime.

It’s notable that principals at the Post declined over the years to embrace the mediacentric interpretation.

Katharine Graham, the Post’s publisher during Watergate, said in 1997, for example:

“Sometimes people accuse us of bringing down a president, which of course we didn’t do. The processes that caused [Nixon’s] resignation were constitutional.”

In 2005, Michael Getler, then the Post’s ombudsman, or in-house critic, wrote:

“Ultimately, it was not The Post, but the FBI, a Congress acting in bipartisan fashion and the courts that brought down the Nixon administration. They saw Watergate and the attempt to cover it up as a vast abuse of power and attempted corruption of U.S. institutions.”

The January article was not the first occasion in which the Times treated the heroic-journalist myth as if it were true.

In an article in 2008 about Woodward’s finally introducing Bernstein to the high-level Watergate source code-named “Deep Throat,” the Times referred to the “two young Washington Post reporters [who] cracked the Watergate scandal and brought down President Richard M. Nixon.”

WJC

Other memorable posts of 2016 :

Chappaquiddick, the docudrama revisiting Senator Ted Kennedy’s misconduct following a late-night automobile accident in July 1969 that killed his 28-year-old female passenger, was released over the weekend to

Chappaquiddick, the docudrama revisiting Senator Ted Kennedy’s misconduct following a late-night automobile accident in July 1969 that killed his 28-year-old female passenger, was released over the weekend to  And yet, there it is: The Post is a hagiographic treatment about a newspaper, the

And yet, there it is: The Post is a hagiographic treatment about a newspaper, the

The quotation has been interpreted as the Times’ giving the Washington Post a

The quotation has been interpreted as the Times’ giving the Washington Post a

The movie was grandiose in its title, “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House.” But its script was a tedious mess that offered no coherent insight into

The movie was grandiose in its title, “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House.” But its script was a tedious mess that offered no coherent insight into

As the veteran Timesman Harrison Salisbury wrote in

As the veteran Timesman Harrison Salisbury wrote in