This essay was first published at the Conversation news site on June 14, 2022, and appears here slightly edited.

In their dogged reporting of the Watergate scandal, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered the crimes that forced Richard Nixon to resign the presidency in August 1974.

That version of Watergate has long dominated popular understanding of the scandal, which unfolded over 26 months, beginning June 17, 1972.

It is, however, a simplistic trope that not even Watergate-era principals at the Post embraced. The newspaper’s publisher during Watergate, Katharine Graham, pointedly rejected that interpretation during a program 25 years ago at the now-defunct Newseum (the “museum of news“) in suburban Virginia.

Nixon quits: Not the Post’s doing

“Sometimes, people accuse us of ‘bringing down a president,’ which of course we didn’t do, and

shouldn’t have done,” Graham said. “The processes that caused [Nixon’s] resignation were constitutional.”

Graham’s words, however accurate and incisive, scarcely altered the dominant popular interpretation of Watergate. If anything, the intervening 25 years have solidified the “heroic-journalist” myth of Watergate, which I dismantled in my media-mythbusting book Getting It Wrong: Debunking the Greatest Myths in American Journalism.

However popular, the heroic-journalist myth is a vast exaggeration of the effect of their work.

Woodward and Bernstein did disclose financial links between Nixon’s reelection campaign and the burglars arrested 50 years ago tomorrow inside the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, in the signal crime of Watergate.

The Watergate complex

They publicly tied Nixon’s former attorney general, John Mitchell, to the scandal.

They won a Pulitzer Prize for the Post.

But they missed decisive elements of Watergate — notably the payment of hush money to the burglars and the existence of Nixon’s White House tapes.

Even so, the heroic-journalist myth became so entrenched that it could withstand disclaimers by Watergate-era principals at the Post such as Graham.

Even Woodward disavowed the heroic-journalist interpretation, once telling an interviewer that “the mythologizing of our role in Watergate has gone to the point of absurdity, where journalists write … that I, single-handedly, brought down Richard Nixon.

“Totally absurd.”

So why not take Woodward at his word? And why has the heroic-journalist interpretation of Watergate persisted through the 50 years since burglars linked to Nixon’s campaign were arrested at the Watergate complex in Washington?

Like most media myths, the heroic-journalist interpretation of Watergate rests on a foundation of simplicity. It glosses over the scandal’s intricacies and discounts the far more crucial investigative work of special prosecutors, federal judges, the FBI, panels of both houses of Congress, and the Supreme Court.

It was, after all, the court’s unanimous ruling in July 1974, ordering Nixon to surrender tapes subpoenaed by the Watergate special prosecutor, that sealed the president’s fate. The recordings captured Nixon, six days after the burglary, agreeing to a plan to deter the FBI from pursuing its Watergate investigation.

The tapes were crucial to determining that Nixon had obstructed justice. Without them, he likely would have served out his presidential term. That, at least, was the interpretation of the late Stanley Kutler, one of Watergate’s leading historians, who noted:

“You had to have that kind of corroborative evidence to nail the president of the United States.”

The heroic-journalist myth, which began taking hold even before Nixon resigned, has been sustained by three related factors.

One was Woodward and Bernstein’s All the President’s Men, the well-timed memoir about their reporting. All the President’s Men was published in June 1974 and quickly reached the top of The New York Times bestseller list, remaining there 15 weeks, through Nixon’s resignation and beyond. The book inescapably promoted the impression Woodward and Bernstein were vital to Watergate’s outcome.

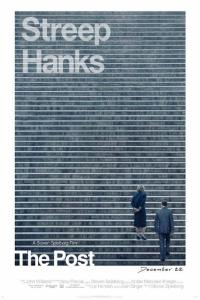

More so than the book, the cinematic adaptation of All the President’s Men placed Woodward and Bernstein at the decisive center of Watergate’s unraveling. The movie, which was released in April 1976 and starred Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, was relentlessly media-centric, ignoring the work and contributions of the likes of prosecutors and the FBI.

The book and movie introduced Woodward’s super-secret source, “Deep Throat.” For 31 years after Nixon’s resignation, Washington periodically engaged publicly in guessing games about the source’s identity. Such speculation sometimes pointed to W. Mark Felt, a former senior FBI official.

Felt brazenly denied having been Woodward’s source. Had he been “Deep Throat,” he once told a Connecticut newspaper, “I would have done better. I would have been more effective.”

The “who-was-Deep-Throat” conjecture kept Woodward, Bernstein and the heroic-journalist myth at the center of Watergate conversations. Felt was 91 when, in 2005, he acknowledged through his family’s lawyer that he had been Woodward’s source after all.

It’s small wonder that the heroic-journalist myth still defines popular understanding of Watergate. Other than Woodward and Bernstein, no personalities prominent in Watergate were the subjects of a bestselling memoir, the inspiration for a star-studded motion picture, and the protectors of a mythical source who eluded conclusive identification for decades.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- How ‘alone’ was WaPo in reporting emergent Watergate scandal? Not very

- WaPo indulges in myth, claims Bernstein’s ‘work brought down a president’

- The Post ‘took down a president’? That’s a myth

- Watergate myth, extravagant version: Nixon was ‘dethroned entirely’ by press

- Hal Holbrook, ‘follow the money,’ and Watergate’s distorted history

- ‘Follow the money’: Why the made-up Watergate line endures

- Cinema and the tenacity of media myths

- Mythmaking in Moscow: Biden says WaPo brought down Nixon

- Media myths, the junk food of journalism

- Every good historian a mythbuster

- Our incurious press

- Getting It Wrong goes on Q-and-A

The quotation has been interpreted as the Times’ giving the Washington Post a

The quotation has been interpreted as the Times’ giving the Washington Post a