Media Myth Alert today marks its 12th anniversary of calling attention to the publication or posting of prominent but exaggerated tales about media prowess and the presumed power and influence of journalists.

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked often-arrogant media outlets such as the Washington Post and PBS, called out media lapses and hypocrisy, and supported the two editions of my myth-busting book, Getting It Wrong.

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked often-arrogant media outlets such as the Washington Post and PBS, called out media lapses and hypocrisy, and supported the two editions of my myth-busting book, Getting It Wrong.

The lineup that unfolds below is admittedly subjective and represents but a slice of the hundreds of essays posted since the launch of Media Myth Alert on the afternoon of Halloween, 2009. It’s nonetheless a slice that makes for pleasant reminiscence. What follows are headlines and descriptions of five of the posts that for varying reasons have stood out over the years:

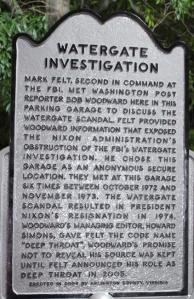

■ Why Trump-Russia is hardly Watergate-Nixon (posted March 5, 2017): Long before the special counsel’s report punctured the notion that then-President Donald Trump conspired with the Russians to steal the 2016 presidential election, Media Myth Alert scoffed at the notion afoot among American journalists that the suspected Trump-Russia scandal was akin to Watergate redux.

“’Overstated’ hardly suffices in describing the media’s eagerness to find in President Donald Trump’s odd affinity for Russia parallels or echoes that bring to mind Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal,” I wrote. “Such stuff is overstated. Premature. Facile. And ahistoric.”

I added: “Casually invoking such parallels is to ignore and diminish Watergate’s exceptionality. Watergate was a constitutional crisis of unique dimension in which some 20 men, associated either with Nixon’s administration or his reelection campaign in 1972, went to prison.

“Watergate’s dénouement — Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 — was driven not by dogged reporting of the Washington Post but by Nixon’s self-destructive decision to tape-record conversations at the White House. Thousands of hours of audiotape recordings were secretly made, from February 1971 to July 1973.” (Disclosing the Watergate tapes was a story the Post missed, by the way.)

I followed up in another post a little more than two months later, writing:

“The murky Trump-Russia suspicions are still far, far from the constitutional crisis that was Watergate, the scandal that took down Richard Nixon’s corrupt presidency and sent some 20 of his associates to jail.”

The Trump-Russia special counsel, Robert Mueller, released his report in May 2019, rejecting suspicions that the Trump campaign or its associates conspired or coordinated with Russia — thus short-circuited eager speculation about a Watergate-type scandal that would bring down a president.

■ WaPo’s ‘five myths’ feature about Vietnam ignores ‘Cronkite Moment,’ Nixon ‘secret plan,’ ‘Napalm Girl’ (posted October 2, 2017): The Washington Post has figured often in posts at Media Myth Alert over the years. A favorite topic has been the newspaper’s unwillingness to explain or take much responsibility for its deeply erroneous reporting about Pfc. Jessica Lynch’s purported heroics early in the Iraq War.

I’ve referred to that reporting as “the most sensational, electrifying, and thoroughly botched front-page story about the early Iraq War.”

In its Sunday editions, the Post runs a fussy feature called “five myths,” a rundown of uneven quality on a fresh topic each week.

In 2017, the newspaper addressed “five Myths” of the Vietnam War — and mentioned none of the prominent media myths of that conflicts. Not the “Cronkite Moment” of 1968, when CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, in an hour-long special report, supposedly swung public opinion against the war. Not the notion Nixon campaigned for the presidency in 1968 on a “secret plan” to end the conflict. Not the myths of the “Napalm Girl” photograph which was taken in June 1972 and supposedly hastened an end to the conflict.

No prominent media myth figured in the Post’s rundown about what it called five “deeply entrenched myths” about Vietnam. Instead, the compilation included such “myths” as: “The refugees who came to the U.S. [after the war] were Vietnam’s elite” and “American soldiers [in Vietnam] were mostly draftees.”

Those were not unimportant aspects of the war. But “deeply entrenched myths”? Certainly not as entrenched as the “Cronkite Moment.” As “Nixon’s secret plan.” As the myths of “Napalm Girl.”

■ It’s like 1948 all over again for American media (posted November 9, 2016): This essay makes the subjective short list because it was a starting point for a project that culminated in publication last year of my seventh book, Lost in a Gallup: Polling Failure in U.S. Presidential Elections.

The “like 1948” essay was posted the morning after Trump’s shocking electoral college victory over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election — an election that Clinton, the news media, and maybe even Trump figured she would win, perhaps decisively.

Truman triumphant, 1948

The depth of surprise on the day after the election brought reminders of the 1948 election, when incumbent Harry S. Truman defeated the odds-on frontrunner, Thomas E. Dewey (see photo nearby of Truman with a Chicago Tribune front page that got it wrong).

In the day-after post, I noted that notable among the misplaced predictions of Clinton’s sure win was that of Stuart Rothenberg, who had written in August 2016 at the Washington Post’s PowerPost blog:

“Three months from now, with the 2016 presidential election in the rearview mirror, we will look back and agree that the presidential election was over on Aug. 9th.

Rothenberg added that “a dispassionate examination of the data, combined with a coldblooded look at the candidates, the campaigns and presidential elections, produces only one possible conclusion: Hillary Clinton will defeat Donald Trump in November, and the margin isn’t likely to be as close as Barack Obama’s victory over Mitt Romney” in 2012.

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

Trump defeated Clinton by 304 electoral votes to 227.

Clinton won the national popular vote on the strength of lopsided support among California voters. She lost the presidency by failing to carry three key Great Lakes states — Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin — where polls and poll-based forecasts suggested she would win clearly, if not overwhelmingly.

Had Clinton won those states, she would have won the White House.

The shock outcome of 2016 is one of eight high-profile polling failures taken up in chapters of Lost in a Gallup.

The book noted that in 2016, “polls and poll-based statistical forecasts had set an election narrative that the news media embraced and locked into place. The final polling estimates showed little to challenge the dominant narrative. The election might be close, but an upset? That seemed implausible.”

Lost in a Gallup quoted Natalie Jackson, the Huffington Post analyst who forecast that Clinton’s chances of winning the presidency stood at 98.2 percent, as saying after the election that “when there are hundreds of polls all saying the same thing — as most polls did when they indicated Clinton would win—it’s easy to develop a false sense of certainty and safety in concluding that that’s what will happen.”

■ ‘They even started wars’: Nonsense in Economist’s holiday double issue (posted December 22, 2012): I’ve noted from time to time at Media Myth Alert how international news outlets are known to invoke prominent myths about American news media.

A notable example was found in the year-end double issue of Britain’s Economist magazine in 2012, in an off-beat essay about the Internet-borne resurgence of cartooning. Embedded in that account was reference to the hoary media myth of yellow journalism. It said:

“In the United States, the modern comic strip emerged as a by-product of the New York newspaper wars between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst in the late 19th century. In 1895 Pulitzer’s Sunday World published a cartoon of a bald child with jug ears and buck teeth dressed in a simple yellow shirt: the Yellow Kid. The cartoon gave the name to the new mass media that followed: ‘yellow journalism.’”

The yellow kid character was a contributing factor in the naming of “yellow journalism.” But not the sole factor.

What attracted the attention of Media Myth Alert was this passage:

“Newspapers filled with sensationalist reporting sold millions. They even started wars.”

They even started wars?

That’s a reference to the myth that in their overheated reporting of Cuba’s rebellion against Spanish colonial rule, the yellow press of Hearst and Pulitzer whipped up war fever to the extent that American military intervention against Spain became inevitable..

The yellow press certainly reported closely about the runup to the Spanish-American War of 1898. But no serious historian believes the newspapers were important factors in bringing about the conflict.

The yellow press certainly reported closely about the runup to the Spanish-American War of 1898. But no serious historian believes the newspapers were important factors in bringing about the conflict.

Simply put, the yellow press did not create, nor was responsible for, the irreconcilable differences that led to war between the United States and Spain.

As I wrote in my 2001 book, Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies:

“The yellow press is not to blame for the Spanish-American-War. It did not force — it could not have forced — the United States into hostilities with Spain over Cuba in 1898. The conflict was, rather, the result of a convergence of [geopolitical and humanitarian] forces far beyond the control or direct influence of even the most aggressive of the yellow newspapers, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.”

■ Adulation for a tyrannical publisher: The Pulitzer documentary on PBS (April 14, 2019): I noted not long ago that “PBS documentaries are nothing if not uneven. … They can promote erroneous interpretations, such as the notion the American press was unwilling to stand up to red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy,” who was the subject of an “American Experience” program in 2020.

PBS documentaries also can give fawning treatment to subjects it regards highly, such as Joseph Pulitzer, the newspaper mogul who endowed the Pulitzer prizes. Pulitzer was, as I wrote in 2019 in reviewing the PBS documentary, “the beneficiary of exceptionally generous biographers.

“Now to that lineup of adulation, we can add the flattery of documentary-filmmakers.”

The PBS documentary was an 83-minute, “mostly hagiographic study of the Hungarian-born Pulitzer who, for a time in the late 19th century, was a dominant figure in New York City newspaper journalism. Pulitzer’s talents and commitments, according to the PBS treatment, were exceptional and endlessly laudatory.”

The effect of all the docu-gushing, I wrote, “was misleading.

“True, Pulitzer led a crowded, remarkable life. He did have a Midas-like touch — he became enormously wealthy as a newspaper champion of the poor, and his riches allowed him to buy opulent homes and live out his infirmity-wracked final years aboard a luxury yacht.

Pulitzer (Library of Congress)

“Pulitzer also was an irritable tyrant who routinely made enemies, who regularly upbraided subordinates, who didn’t think much of his three sons, and whose wife worked like a slave to please him. This darker side to Pulitzer wasn’t entirely ignored in the program …. It just wasn’t examined in much revealing depth.

“In the end Pulitzer’s failings, personal and journalistic, were mostly excused.”

For years, Pulitzer ran the World by remote control, as an absentee owner. “From retreats in Maine, Georgia, and Europe,” I wrote, “Pulitzer fired off a steady stream of telegrams and letters of instruction, guidance, and reproach to his editors and managers. The correspondence reveals a harsh, bullying, and dictatorial side to Pulitzer,” noting that “the effects and implications of Pulitzer’s long absences, infirmities, and distant management were not much explored” by PBS.

The topic is not insignificant because the closing years of the 19th century gave rise to one of the most controversial and poorly understood periods in American media history — the rise of yellow journalism and the at-times exaggerated reporting of the Spanish-American War and its antecedent events.

More memorable posts at Media Myth Alert:

- In essay about fake news, Vox offers up media myth of the ‘Napalm Girl’

- Jon Krakauer rolls back claims about WaPo ‘source’ in Jessica Lynch case

- WaPo, Helen Thomas, and Nixon’s ‘secret plan’

- PBS squanders opportunity to offer ‘content that educates’ in ‘War of the Worlds’ doc

- Suspect Murrow quote pulled at Murrow school

- That’s rich: Woodward bemoans celebrity journalism

- Mythmaking in Moscow: Biden says WaPo brought down Nixon

- WSJ columnist, trying to explain Trump, trips over Cronkite-Johnson myth

- Chris Matthews invokes the ‘if I’ve lost Cronkite’ myth in NYT review

- ‘Bras were never burned at ’68 Miss America Pageant’? Might want to check that, ‘Time’

- ‘Fake news about fake news’: Enlisting media myths to condemn Trump’s national emergency

- Insidious: Off-hand references signal deep embedding of prominent media myths

- Why history is badly taught, poorly learned

- The shame of the press

- Media myths, the ‘junk food of journalism’

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

“Fake news” has plenty of antecedents in mainstream media — several cases of which are examined in my mythbusting book,

“Fake news” has plenty of antecedents in mainstream media — several cases of which are examined in my mythbusting book,  fiercely in the ambush of her unit during the early days of the Iraq War in 2003. Lynch, the

fiercely in the ambush of her unit during the early days of the Iraq War in 2003. Lynch, the