The most famous seven words in American journalism — “All the news that’s fit to print” — took a permanent place 115 years ago yesterday in the upper left corner, or left “ear,” of the New York Times masthead.

And I recalled that occasion in a piece for the BBC News online site, writing:

“The motto appeared on the Times’ front page without notice, commentary, or fanfare. In the years since, the phrase has been admired as a timeless statement of purpose, interpreted as a ‘war cry’ for honest journalism, and scoffed at as pretentious, overweening, and impossibly vague.

“Even the Times hasn’t been entirely consistent in its embrace and interpretation of those seven words. In 1901, at the 50th anniversary of its founding, the Times referred to ‘All the news that’s fit to print’ as its ‘covenant. In 2001, a Times article commemorating the newspaper’s 150th anniversary said of the motto:

“’What, exactly, does it mean? You decide. The phrase has been debated, and endlessly parodied, both inside and outside the Times for more than a century.’

“On occasion, the motto has been taken far too seriously, as in 1960 when Wright Patman, a U.S. congressman from Texas, asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether ‘All the news that’s fit to print’ amounted to false and misleading advertising.

“’Surely this questionable claim has a tendency to make the public believe, and probably does make the public believe, that the New York Times is superior to other newspapers,’ Patman wrote.

“The Trade Commission declined to investigate, saying: ‘We do not believe there are any apparent objective standards by which to measure whether “news” is or is not “fit to print.”’

“No matter how it’s interpreted, the motto certainly is remarkable in its permanence. One-hundred fifteen years on the front page has invested the motto with a certain gravitas. It often has been associated with fairness, restraint, and impartiality — objectives that nominally define mainstream American journalism.

“A commentary in the Wall Street Journal in 2001 addressed those sentiments, describing the motto as the ‘leitmotif not merely for the Times, but also, by a process of osmosis and emulation, for most other general-interest papers in the country, as well as for much of the broadcast media.

“Interestingly, the ‘leitmotif’ of American journalism had its origins in marketing and advertising.

“’All the news that’s fit to print’ first appeared on an illuminated advertising sign, spelled out in red lights above New York’s Madison Square in early October 1896. That was about six weeks after Adolph S. Ochs had acquired the newspaper in bankruptcy court.

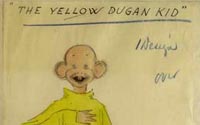

“Ochs, patriarch of the family that still controls and publishes the Times, had come to New York from Tennessee. His task was to differentiate the Times from its larger, aggressive, and wealthier rivals — notably the yellow press of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. It was a tall order, given the beleaguered status of the Times in New York’s crowded newspaper market.

“Ochs possessed a keen sense of promotion and turned to a number of techniques to call attention to the Times. The illuminated sign at Madison Square was one. An even more successful promotion was a contest inviting readers to propose a better motto.

“In late October 1896, the Times announced it was offering $100 for the phrase of ten words or fewer that ‘more aptly’ captured the newspaper’s ‘distinguishing characteristics’ than ‘All the news that’s fit to print.’

“Hundreds of entries poured in. … As the contest unfolded in the fall of 1896, the Times amended the rules, making clear it would not abandon ‘All the news that’s fit to print’ but would still pay $100 for the best suggestion. And entries kept coming in.

“A committee of Times staff narrowed the field to 150, which in turn was winnowed to four by the motto contest judge, Richard W. Gilder, editor of The Century magazine. The finalists were:

- “Always decent; never dull”

- “The news of the day; not the rubbish”

- “A decent newspaper for decent people”

- “All the world’s news, but not a School for Scandal”

“The latter entry, Gilder determined, was the best of the lot, and the Times paid the prize money to the author of the phrase, D.M. Redfield of New Haven, Connecticut.

“What exactly prompted Ochs to move ‘All the news that’s fit to print’ to the front page 115 years ago is not entirely clear. But his intent was unmistakable — to throw down a challenge to the yellow press, a challenge that Ochs ultimately won. The Times has long outlived the New York newspapers of Hearst and Pulitzer.

“So the motto lives on as a reminder, as a daily rebuke to the flamboyant extremes of fin-de-siècle American journalism that helped inspire ‘All the news that’s fit to print.'”

Recent and related:

- 114 years on the front page

- Keller no keeper of the flame on famous NYTimes logo

- Yellow journalism: Back story to a sneer, 115 years on

- The ‘anniversary’ of a media myth: ‘I’ll furnish the war’

- Two myths and today’s New York Times

- Fact-checking Keller on NYT-Bay of Pigs suppression myth

- More than merely sensational

- Media myths, the ‘junk food of journalism’

- ‘Persuasive and entertaining’: WSJ reviews ‘Getting It Wrong’