This essay was first published at The Conversation news site on June 2, 2022, and appears here slightly edited.

The “Napalm Girl” photograph of terror-stricken Vietnamese children fleeing an errant aerial attack on their village — taken 50 years ago today — has rightly been called “a picture that doesn’t rest.”

‘Napalm girl,’ 1972 (Nick Ut/AP)

It is one of those exceptional visual artifacts that draws attention and even controversy years after it was made.

Last month, for example, Nick Ut, the photographer who captured the image, and the photo’s central figure, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, made news at the Vatican as they presented a poster-size reproduction of the prize-winning image to Pope Francis, who has emphasized the evils of warfare.

In 2016, Facebook stirred controversy by deleting “Napalm Girl” from a commentary posted at the network because the photograph shows the then-9-year-old Kim Phuc entirely naked. She had torn away her burning clothes as she and other terrified children ran from their village, Trang Bang, on June 8, 1972. Facebook retracted its decision amid an international uproar about the social network’s free speech policies.

Such episodes signal how “Napalm Girl” is much more than powerful evidence of war’s indiscriminate effects on civilians. The Pulitzer Prize-winning image, formally known as “The Terror of War,” has also given rise to tenacious media-driven myths.

Media myths are those well-known stories about or by the news media that are widely believed and often retold but which, under scrutiny, dissolve as apocryphal or wildly exaggerated.

The distorting effects of four media myths have become attached to the photograph, which Ut made when he was a 21-year-old photographer for the Associated Press.

Prominent among the myths of the “Napalm Girl,” which I address and dismantle in my book Getting It Wrong: Debunking the Greatest Myths in American Journalism, is that U.S.-piloted or guided warplanes dropped the napalm, a gelatinous, incendiary substance, at Trang Bang.

Not so.

The napalm attack was carried out by propeller-driven Skyraider aircraft of the South Vietnamese Air Force trying to roust communist forces dug in near the village – as news accounts at the time made clear.

The headline over the New York Times report from Trang Bang said: “South Vietnamese Drop Napalm on Own Troops.”

The Chicago Tribune front page of June 9, 1972, stated the “napalm [was] dropped by a Vietnamese air force Skyraider diving onto the wrong target.”

Christopher Wain, a veteran British journalist, wrote in a dispatch for United Press International: “These were South Vietnamese planes dropping napalm on South Vietnamese peasants and troops.”

The myth of American culpability at Trang Bang began taking hold during the 1972 presidential campaign, when Democratic candidate George McGovern referred to the photograph in a televised speech. The napalm that badly burned Kim Phuc, he declared, had been “dropped in the name of America.”

McGovern’s metaphoric claim anticipated similar assertions, including Susan Sontag’s statement in her 1973 book “On Photography,” that Kim Phuc had been “sprayed by American napalm.”

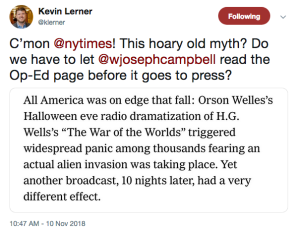

(The Associated Press, in an article posted online yesterday, erroneously described the aerial attack at Trang Bang as “an American napalm strike on a Vietnamese hamlet.” See screenshot nearby. The news agency later in the day corrected the error after it was noted on Twitter.)

Two other, related media myths rest on assumptions that “Napalm Girl” was so powerful that it must have exerted powerful effects on its audiences. These myths claim that the photograph hastened an end to the war and that it turned U.S. public opinion against the conflict.

Neither is accurate.

Although most U.S. combat forces were out of Vietnam by the time Ut took the photograph, the war went on for nearly three more years. The end came in April 1975, when communist forces overran South Vietnam and seized its capital.

Americans’ views about the war had turned negative long before June 1972, as measured by a survey question the Gallup Organization posed periodically. The question – essentially a proxy for Americans’ views about Vietnam – was whether sending U.S. troops there had been a mistake. When the question was first asked in summer 1965, only 24% of respondents said yes, sending in troops had been a mistake.

But by mid-May 1971 – more than a year before “Napalm Girl” was made – 61% of respondents said yes, sending troops had been mistaken policy.

In short, public opinion turned against the war long before “Napalm Girl” entered popular consciousness.

Another myth is that “Napalm Girl” appeared on newspaper front pages everywhere in America.

Front page here, but not everywhere

Many large U.S. daily newspapers did publish the photograph. But many newspapers abstained, perhaps because it depicted frontal nudity.

In a review I conducted with a research assistant of 40 leading daily U.S. newspapers – all of which were Associated Press subscribers – 21 titles placed “Napalm Girl” on the front page.

But 14 newspapers – more than one-third of the sample – did not publish “Napalm Girl” at all in the days immediately after its distribution by AP. These included newspapers in Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Houston and Newark.

Only three of the 40 newspapers examined – the Boston Globe, the New York Post and the New York Times – published editorials specifically addressing the photograph. The editorial in the New York Post, then a liberal-minded newspaper, was prophetic in saying:

“The picture of the children will never leave anyone who saw it.”

More from Media Myth Alert:

- 40 years on: The ‘napalm girl’ photo and its associated errors

- NYTimes ignores former senior AP journalists seeking correction on ‘napalm girl’ context

- A sort-of correction from the New York Times

- No, ‘Forbes’: It wasn’t ‘an American napalm attack’

- ‘Scorched by American napalm’: The media myth of ‘Napalm Girl’ endures

- Piling on the media myths: Claiming ‘energizing’ power for ‘Napalm Girl’ photo

- Mythmaking in Moscow: Biden says WaPo brought down Nixon

- The shame of the press

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked

Twelve years offers a fitting occasion to recall some memorable posts — posts that tweaked

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

Obama defeated Romney by an electoral count of 332-206.

The movie was grandiose in its title, “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House.” But its script was a tedious mess that offered no coherent insight into

The movie was grandiose in its title, “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House.” But its script was a tedious mess that offered no coherent insight into