I’m not much a fan of the work of David McCullough, the award-winning popular historian whose latest book is the well-received The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris.

I’m not much a fan of the work of David McCullough, the award-winning popular historian whose latest book is the well-received The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris.

I couldn’t get through McCullough’s acclaimed 1776, a military history of a decisive year in American life that oddly had little to say about the Declaration of Independence.

But McCullough, in an interview published in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, offered several provocative and telling points about why American history is so badly taught and so poorly grasped.

The splintered state of historical studies is one of the factors, McCullough said, adding:

“History is often taught in categories — women’s history, African American history, environmental history — so that many of the students have no sense of chronology. They have no idea what followed what.”

That’s a fair point. History by interest group can be an invitation to incoherence.

McCullough also pointed out that textbooks on history tend to “so politically correct as to be comic. Very minor characters that are currently fashionable are given considerable space, whereas people of major consequence … are given very little space or none at all.”

What’s more, as McCullough noted, textbooks often are tedious, boring, and poorly written. Historians by and large “haven’t learned to write very well,” McCullough wrote.

Although McCullough didn’t mention this in the interview, learning history can be frustrating because history is prone to error, distortion, and myth.

History quite simply can be myth-encrusted — and unlearning the myths of history can be challenging, time-consuming, and often unrewarding.

As I discuss in Getting It Wrong, my media-mythbusting book that came out last year, myths in history spring from many sources, including the timeless appeal of the tale that’s simple and delicious.

A telling example is the undying tale about William Randolph Hearst’s purported vow in an exchange of telegrams with Frederic Remington to “furnish the war” with Spain at the end of the 19th century.

As I discuss in Getting It Wrong, among the many reasons for doubting that anecdote are Hearst’s denial and the absence of any supporting documentation. The Remington-Hearst telegrams have never surfaced.

But the tale lives on, as an appealing yet exceedingly simplified explanation about the causes of the Spanish-American War and as presumptive evidence of Hearst’s madcap and ethically compromised ways.

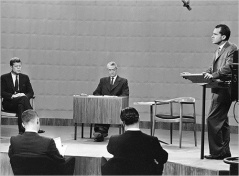

The urge to simplify history also explains the tenacity of the so-called “Cronkite Moment” of 1968, when the CBS News anchorman’s assessment of the Vietnam War as a “stalemate” supposedly prompted President Lyndon Johnson to realize the folly of his war policy and not to seek reelection.

However, as I discuss in Getting It Wrong, Johnson did not see the program when it aired, and Cronkite until late in his life claimed his “stalemate” assessment had at best modest influence, that it was “another straw on the back of a crippled camel.”

And even that effect was probably exaggerated.

But the notion that the “Cronkite Moment” was powerful and decisive has been promoted by many historians, notably David Halberstam in his error-riddled The Powers That Be.

The cinema, too, often injects error and misunderstanding into historical topics.

Hollywood’s treatment of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s investigative reporting for the Washington Post is an important reason why many people erroneously believe that Woodward and Bernstein brought down Richard Nixon’s corrupt presidency.

Good history and successful cinema are quite often at odds, as Richard Bernstein noted in a memorable essay published several years ago in the New York Times.

“Artists who present as fact things that never happened, who refuse to allow the truth to interfere with a good story, are betraying their art and history,” Bernstein wrote.

So there are plenty of reasons beyond McCullough’s useful observations as to why American history is so poorly understood.

It may always be that way. After all, as the Scottish historian Gerard De Groot has noted, history is “what we decide to remember.

“We mine the past,” he has written, “for myths to buttress our present.”

Recent and related:

- Every good historian a mythbuster

- ‘Too early to say’: Zhou was speaking about 1968, not 1789

- Woah, Wapo: Mythmaking in the movies

- ‘The newspaper that uncovered Watergate’?

- ‘War Lovers’: A myth-indulging disappointment

- Halberstam the ‘unimpeachable’? Try myth-promoter

- Area 51 book offers implausible, myth-based tale

- Helen Thomas and the Iraq War: What’s she talking about?

- Recalling the mythical ‘Cronkite Moment’

- ‘Mired in stalemate’? How unoriginal of Cronkite

- Why they get it wrong

- Media myths, the ‘comfort food’ of journalism

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ wins SPJ award for Research about Journalism

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ launched at Newseum